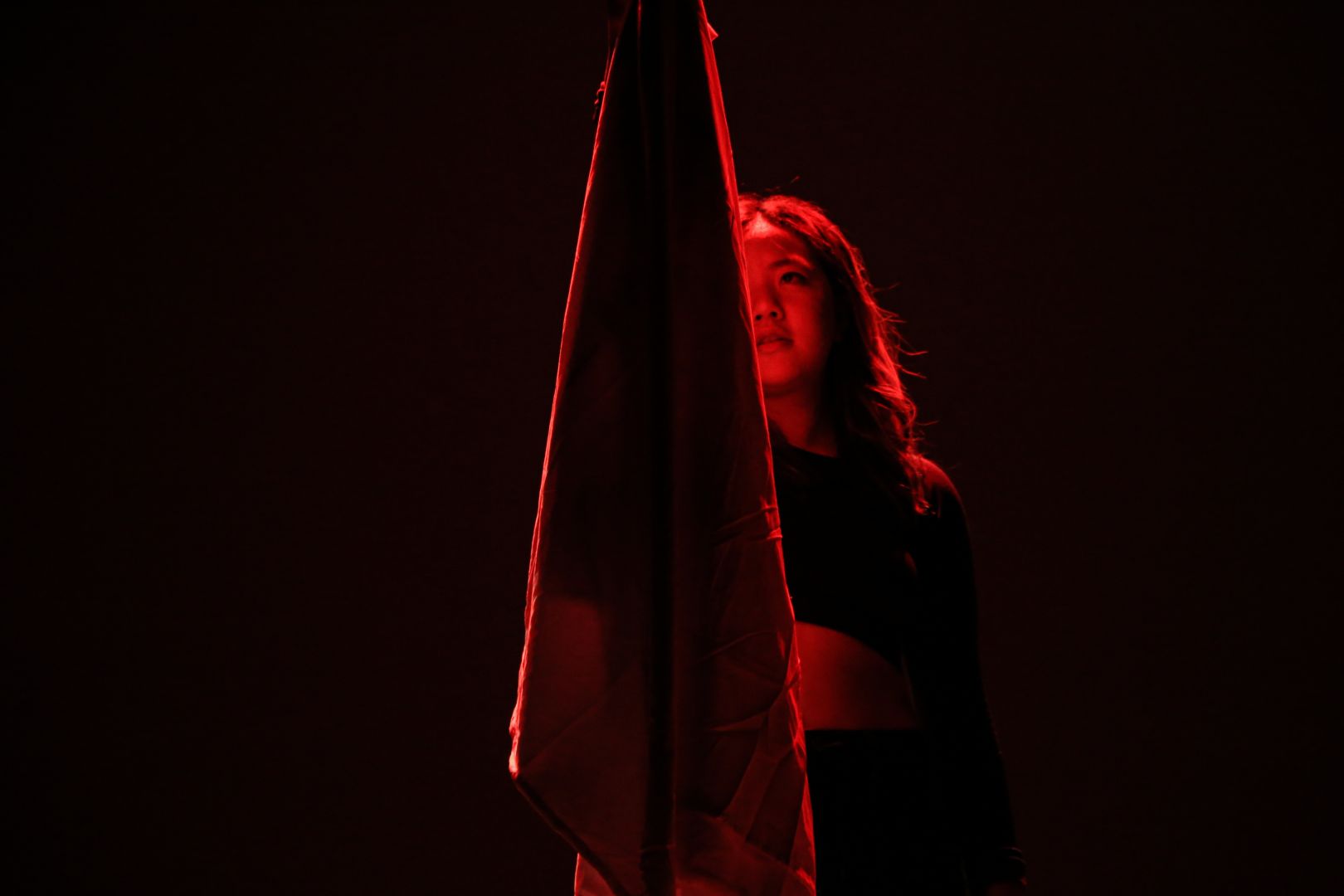

Meet Ariel Urim Chung | Oral Historian & Artist

We had the good fortune of connecting with Ariel Urim Chung and we’ve shared our conversation below.

Hi Ariel Urim, where are your from? We’d love to hear about how your background has played a role in who you are today?

Hi! My name is Ariel Urim Chung (she/her), and I am an oral history scholar and artist based in New York City/the unceded lands of the Lenni-Lenape people. There are many fabrics that make who I am today. Now I have been introduced to you as a scholar and artist, but at various points in my life, I was (or still am) a painter, an actor, a theatre director, a trouble-maker, a foreigner, and many in-between. As a multi-hyphenate, I believe the labels do not entirely tell what we wish to be or do, but moments and memories may offer a better understanding. So I am here to tell you about a memory that has re-framed me as I became an adult, growing older into the women I saw the most growing up.

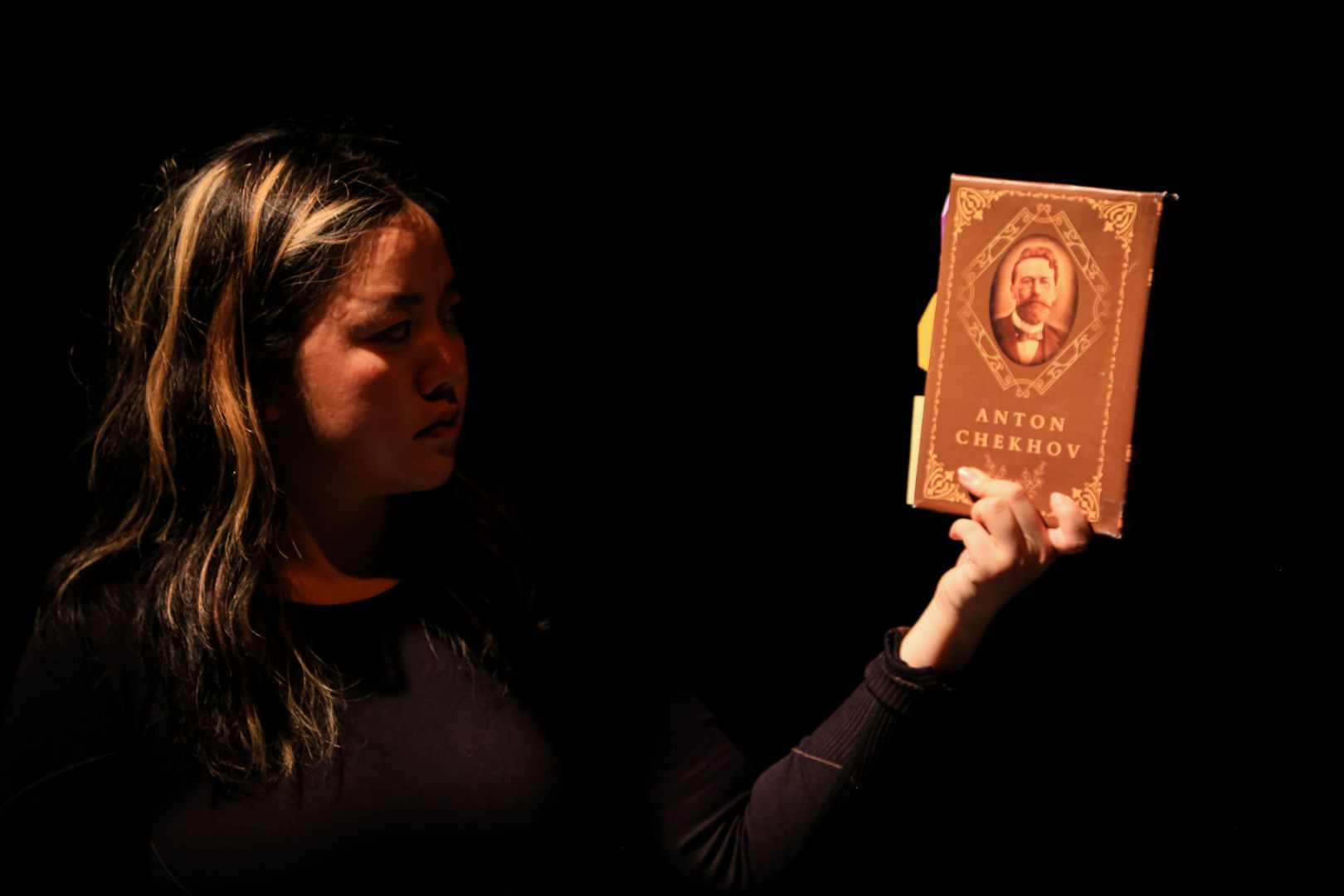

There are few things I remember of holidays–especially New Year’s. On my mother’s side, no women were allowed to cook. To be clear, most of them already had spent days cooking for their husbands’ families. Between the six Choi sisters and their daughters, it was an unspoken rule that no more cooking would happen in the company of each other. Instead, there were potlucks of store-bought food and dishes from home. Each sister was in charge of one dish: whether that was cake, fish, or meat, the formula kept intact. In this household, gendered labor appeared rather in the gifts of education. My early exposure to scholarship blossomed by these six fierce women: musicians, painters, translators, and literary scholars who gifted me books to fill up my room. The youngest of them all is my mother.

Later in life, I have learned a longer history of these women and my legacy as a scholar placed in between the complicated relationship between the Korean peninsula and the United States. I won’t say more, but my research and creative practice derive closely from my lived experience as a woman, diasporic, and daughter of the aforementioned people. It has brought me to view immigration as fluid, scholarship as liberation, care as political, and war as personal. The grandiosity of oppression is told between the casual conversations at the potluck dining table that inform my practice as an oral historian and scholar.

To be an artist, or to call myself an artist, has been something of conflict over the years. Same went for calling myself a scholar. The more I dived into the question of what it means to be an ‘artist’ (there was I point I denounced that), I thought the borders between a ‘creative’ career and that is not is something quite difficult to delineate especially when my ‘official positional title’ was not ‘full-time artist’ at that moment. I’ve returned to school in a social science studies program, and found a practice I felt ever close to in what I call ‘creative.’ Perhaps being an artist is a way of living life, rather than where our monetary income derives from or what we produce. And sometimes I lose that! There will be times I call myself an artist, but also do not feel like one until that moment comes back to me. It’s hard to describe what that moment feels like, but it’s like being unstuck–being able to breathe into my body, and transforming what I am feeling into something outward. Then I get stuck again. And unstuck. It’s a repetition.

To be honest, I miss performing (I was a theatre major in college). I still write plays because it’s where I can reserve myself to consider this practice for myself and for no one else.

Can you open up a bit about your work and career? We’re big fans and we’d love for our community to learn more about your work.

I am currently leading The Kitchen Project, an oral history project recording diasporic Asian mothers, daughters, and non-binary children on food, maternal figures, and care. My work in this project is as an oral historian. It’s difficult to fully capture what an oral historian does in one sentence, but it encompasses a combination of: talking and listening to people, archival research, audio editing, transcribing, indexing, archiving, and curating the oral histories. The project stemmed out of a difficult period in the remnants of Covid-19 when there was a clear desire for ‘Asian’ food (especially on social media) yet exponentially increased Asian hate crimes. I was viscerally uncomfortable with this; it felt like our bodies were displayed for public consumption. And this is not quite new–Asians in the United States have been continuously racialized through food. Often when I talk about ‘Asian’ food or largely food culture, people’s reaction is often an ‘ooh’ and ‘aah’ and how much food brings people together! Being a huge foodie who cares for my loved ones through cooking for them, I agree and also want to point out how much this conversation underplays the power that food holds in systems of oppression. Food is a medium that viscerally connects the interior and exterior of our bodies–affects like disgust and desire are seeped into how we view food prepared and consumed by those different from us.

But at the end of the day, we gotta eat to survive. More importantly, as a child growing up in a patriarchal society, many femmes I knew spent a lot of time in the kitchen, with much more complicated stories than a simple narrative of gender roles. These memories in the kitchens, and even after I became an adult, created affinity spaces for me. So the project is a love letter to the people who made me, an acknowledgement that much of our unseen labor is the backbone of the care infrastructures and we are always in debt to each other–whether that is a tupperware of food or an invitation to someone’s home. I record stories of people who are stay-at-home-moms, or young adults who are just starting their lives, or people who chose not to cook, or people who love to cook, or really anyone who has a say in their life as a femme diasporic Asian mother, daughter, or non-binary child. The oral histories record the many lives in the kitchens, in the efforts of complicating our collective memory of maternal figures, immigration, and care.

The project is currently funded by Brown Institute of Media Innovation and supported by my position as a visiting scholar at NYU’s Asian/Pacific/American Institute. The project is heading in many directions but currently we are focusing on creating a public facing digital archive. I am really excited about where the project is heading!

I regard an oral historian as a memory worker, a historian, a listener, a storyteller–all the above. It’s never what I thought I would see myself in, but surely being an artist has encouraged me to navigate life through different titles. It was always difficult to define what my creative practice is because the medium has continuously changed. This project was a significant part in turning around my practice because it helped me articulate not my medium but a thread in the stories that attract me. I continuously look for intimate first-person narratives that may theorize, complicate, and teach us more about systemic oppressions and how they relate in real life.

Any places to eat or things to do that you can share with our readers? If they have a friend visiting town, what are some spots they could take them to?

I absolutely love taking folks around for a little history tour of Chinatown in Manhattan; I always relate much better to the geography when I learn even a little more about the history of the land I stand on. I don’t claim to be an expert, but I’ve learned much through Chinatown cultural workers’ activism in the recent years after moving to Manhattan. First moving into New York from North Carolina, seeing a predominantly geographically Asian community in the United States was mind-boggling. Especially the community organizing against gentrification and longevity in Chinatown has been an inspiration in my envisioning of a blend of creative, community-centered, and academic practice.

Shoutout is all about shouting out others who you feel deserve additional recognition and exposure. Who would you like to shoutout?

My library will always tell you where my thinking comes from! I have my ‘Avengers’ of thinkers who have educated me with their words. As an artist currently living, I believe that we often forget the living artists that continuously are making the fabric of our communities. I am always deeply grateful for lifelong friendships that not only uphold me in my personal life but also influence me in my creative practice. Whether they are late night tea talks or meetings in the rehearsal room, these people continuously build me daily, challenging my perception of creative practice. These are some people, whose work I very briefly redacted into few words, who Shoutout LA should know more about: Anthony Sertel Dean (sound artist), Miguel Donado (graphic designer), Begum “Begsy” Inal (dramaturg), Chaesong Kim (director), and Khôi Nguyên Trinh (poet).

Website: www.arielurimchung.com

Instagram: a_real_a_riel

Image Credits

Anthony Sertel Dean, Carol Rosegg, and Jayon Park (names indicated on image titles)