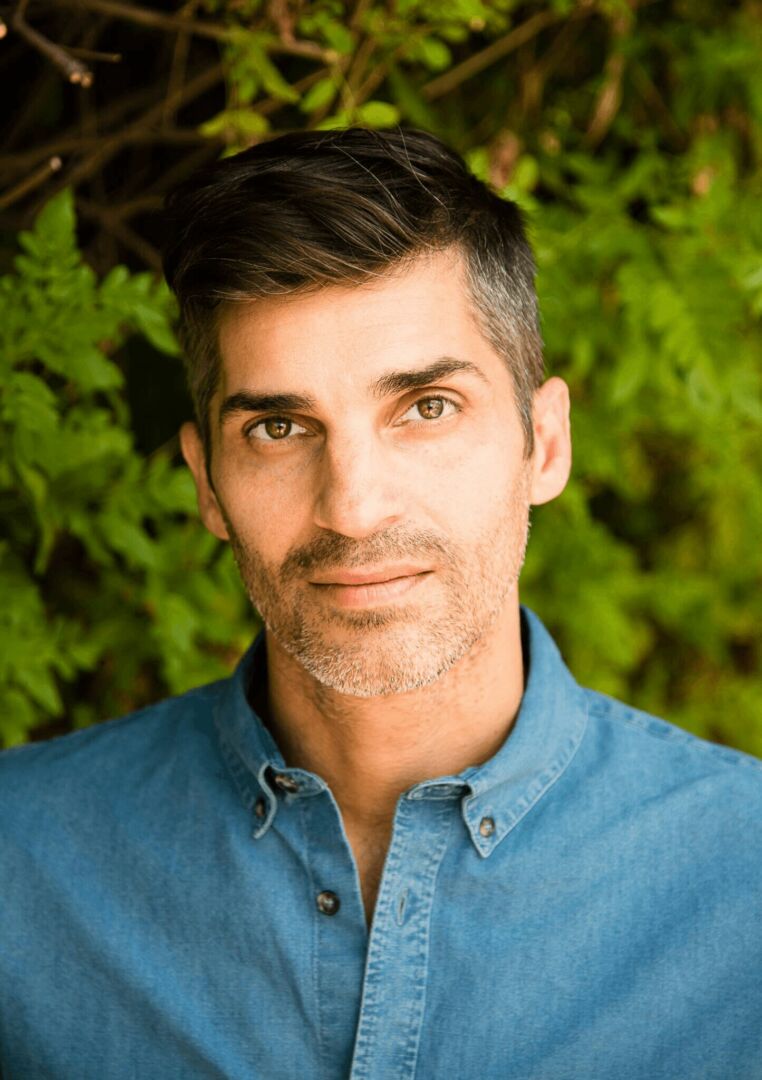

Meet Blas Falconer | Poet, Editor, and Professor

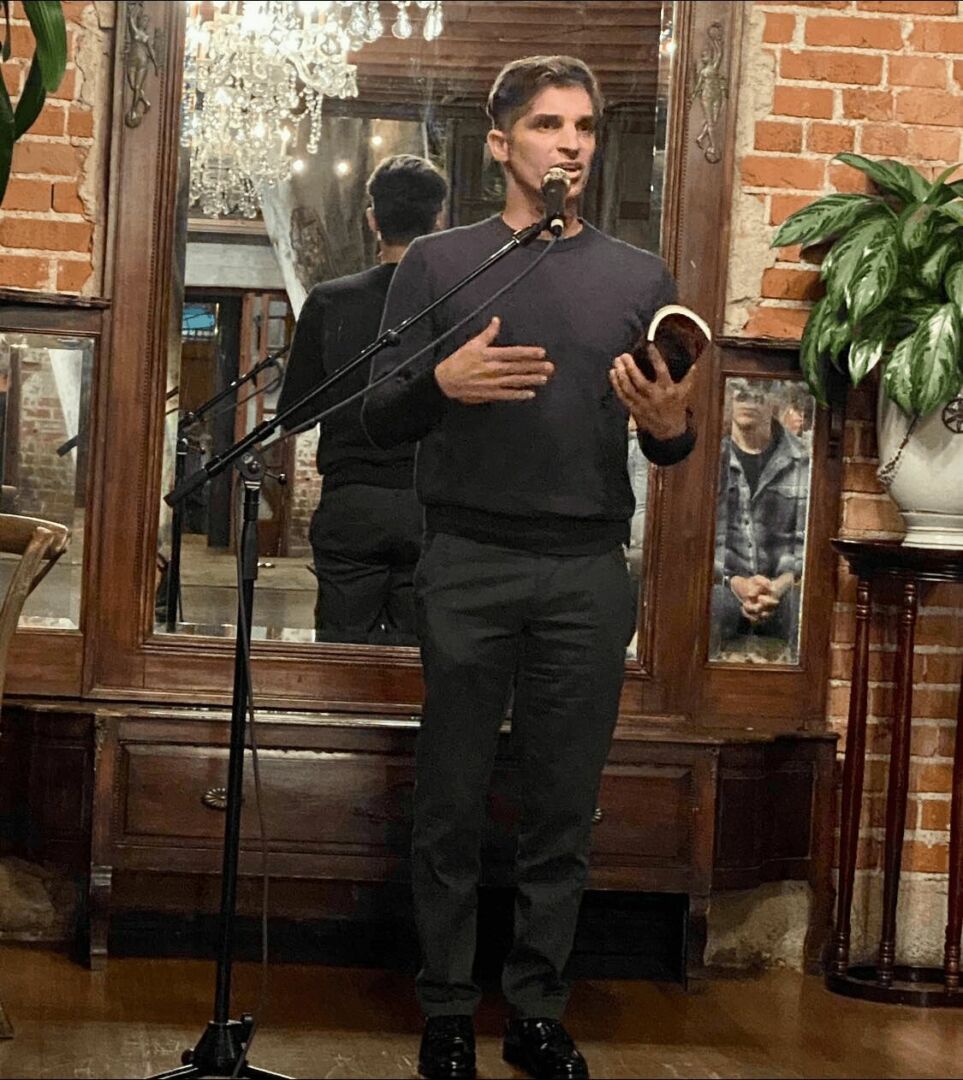

We had the good fortune of connecting with Blas Falconer and we’ve shared our conversation below.

Hi Blas, can you share the most important lesson you’ve learned over the course of your career?

I first encountered contemporary poetry in an advanced English class during my senior year of college and began writing soon after. I was still in the closet and would be for three more years, so reading and writing poetry was a deeply private experience, at first, that I found profoundly rewarding. To write poetry meant to honor my own voice. To write poetry meant to be sensitive to the conflicts at odds within me for most of my life. To write was to actively seek clarity and understanding, for the first time, really, through introspection and not from those around me. Once I started, I knew that I wanted to write poetry for the rest of my life, and I quickly learned that literary contests could be instrumental in helping me to achieve this aim.

During my seven years of graduate school, various awards and prizes became a way of supporting my studies, and perhaps more importantly validating and nurturing the voice and the perspective that I had not acknowledged openly until then. After graduate school, I sought and was fortunate enough to find a tenure track position, teaching poetry. Various competitions allowed me to not teach over the summer, and to instead complete the manuscript for my first book. Competitions helped me pay off debts that had accrued over the years in school and hire childcare when I needed it to complete my second book of poems, which was published, albeit indirectly, because of a competition award. Awards played an important role in securing tenure and promotion at work. Professionally, I had done everything that I could in an effort to support my writing life, and I was profoundly grateful to the competitions that had helped me accomplish this goal.

There are so many ways in which these awards shape the poetry world. Many first books are published through competitions. Competitions bring attention to writers within marginalized communities to reflect the diversity of voices within the arts. Competitions often support journals and presses that might otherwise not be able to keep their doors open.

Although it seems ungrateful to say anything negative about the proliferation of creative writing awards, there are ways in which competitions also complicate matters. What strikes me as the most challenging aspect of competitions and the professionalization of creative writing in general is how easy it is, as we become more and more focused on awards for publication, for financial support, and for outside validation, to lose sight of why we are writing, placing professional rewards above the personal rewards.

As time went on, my writing became more and more entangled with my career as a teacher and as an editor, until my professional life wasn’t supporting my writing life, but the other way around. Awards are a kind of currency to secure the coveted tenure teaching position, tenure and promotions, the raise or sabbatical, readings, festivals, more awards, more fellowships, until there seemed to be an inverse correlation between the amount of time that I spent seeking support, and how much pleasure that I took in writing. Writing brought me anxiety, then, not satisfaction or insight as I moved further and further from that internal voice, that quiet voice that led me to poetry in the first place. Finally, I had to make a decision, begin writing again without consideration of what would happen after the poems were written or quit writing altogether.

I chose the former, slowly disentangling my writing from my profession. I quit my job. I stopped sending to journals, stopped sending to competitions. And I started writing, not showing the work, at first, to anyone, not thinking of a longer project, a book. I was turning inward, again, writing for the sake of writing, one poem at a time. And eventually it began to feel the way it had when I first started. Trusting myself. Guided by own voice.

Eventually, I started sending my poetry to journals and competitions but more cautiously, more thoughtfully and far more infrequently, not letting myself think too seriously about what it meant professionally to get an acceptance or a rejection. I started sending to competitions, but never writing toward a competition and only if the award seemed fitting for the work that I had already done. And after a few years, I started putting the poems together, thinking about a larger project to send out, and the experience, again, was personal and intuitive. And I told myself that even if it didn’t get published and if it didn’t win awards, it was still worth the experience. That writing the poems, putting them together, that accomplishment was the reward.

If you keep a secret about yourself for much of your life for fear of your life, for fear of rejection, humiliation, and violence, then to speak your truth, even a simple gesture of love, can feel like a revolutionary act, a validation of oneself, questioning the systems of power that would silence you. And if poetry has the potential to be the most thoughtful speech that one can utter, “the best words in their best order,” then amid all the blather and bathos, I still believe that the poem can distill and magnify the diminished voices of those who might otherwise be erased.

It turns out, that what threatens to silence isn’t always some oppressive power outside of the writer, but the writer themselves. In my case, at least, it was a quickly growing desire for validation, which I’m convinced stems from, ironically, the sense of having been silenced for the first twenty five years of my life and what led me to poetry in the first place. I guard against these, first and foremost, now, protective of what brings me back to the page, what rings true to me, because if I lose that, then I’ve lost everything, no matter what anyone else says or how many awards I win.

Let’s talk shop? Tell us more about your career, what can you share with our community?

Although I grew up in the suburbs of Washington D.C., removed from any Latinx community, I spent most summers with my grandmother in Salinas, Puerto Rico, where everyone seemed related, somehow, and probably was, considering how many generations my mother’s family lived in this small town. Free to do what we wanted, my sister, my brother, my cousins, and I spent our days galavanting in the streets. We palmed quarters from my grandmother’s dresser to play pinball in the local bar, where older gentlemen sat at dominoes for hours.

Most days, we hitched rides to the beach in the beds of trucks. There, we lounged in the hammock, telling stories, went swimming or sailing, watched fishermen on the pier. We picked passion fruit from my uncle’s roof, or begged one of the older boys to climb the great tree and collect quenepas, Spanish limes, our favorite. At dusk, we wandered into the kitchen of my grandmother’s restaurant, where we always found her with her sister and the other women, preparing orders onto large silver trays, plate after plate.

When my grandmother locked the restaurant doors each night, she came home, got in bed and spent her last waking minutes reading from one of several books on her side table. Thumbing through them, I was always curious by the range of subject, genre, and language, though I had only ever heard her speak Spanish with any fluency. Some nights, I would knock on her door, and she would invite me onto the bed to talk about the day. If she liked what she was reading, she would become animated, again, despite the many hours on her feet, and go into great detail about the author and the work itself.

On one memorable occasion, my grandmother was reading Yerba Bruja (Bewitched Herb), a book of poems by the Puerto Rican activist Juan Antonio Corretjer. Born in 1908, Corretjer was raised within a pro-Independence family. As he grew up, he attended rallies, joined political youth organizations, and wrote poetry on behalf of the cause, a cause that my grandmother, born nine years after Corretjer, also supported.

In the 1957 publication of this poetry collection, Corretjer uses the plant as a metaphor, my grandmother explained, sitting up in bed. The poet had opened a book, she said slowly in a Spanish that I could understand, and found a leaf that had been used to mark the page. Corretjer was surprised to see that the leaf had continued to grow after it was pulled from the stem, just as Puerto Rico would grow after ties with the United States were broken. In this way, yerba bruja became a patriotic symbol for Puerto Ricans. Just a child, I was enchanted by the figurative language’s power to articulate something so personal and profound, to define and champion a perspective that others would recognize as somehow “true” in their own lives.

When I was a little older, my grandmother introduced me to the poems of Julia de Burgos, another Puerto Rican Independent, who spoke out against U.S. influence. One summer evening, after closing the restaurant early, we went to a small video store in the plaza to pick out a movie. As I was scanning the shelves in the small room for an American film, my grandmother spotted a documentary on de Burgos. That night we sat close to my grandmother’s small television to listen to poetry, as various grainy images of town plazas and landscapes flashed upon the screen. As with much of Corretjer’s poetry, de Burgos often turned to the landscape to convey a sense of national pride. “Flood my spirit,” she writes in “The Great River Loiza,” one of her most famous poems.

As much as I admired the work and my grandmother’s spirit, I wasn’t drawn to the cause as much as I was drawn to the medium, how they spoke to the cause—how the subject was rendered, in the leaf, in the river. And so when I began to write poems, I found myself seeking other poets who wrote in English, poets who I might identify as models of my own.

First, I turned to Nuyorican poets, who shared, at the very least, a history with the island of Puerto Rico and with two languages. Bob Holman, in Aloud, described Nuyorican Poetry as a “SHOUT,” a contact sport. Miguel Algarin wrote, “The language of poetry is now associated with the great mass of people who are suffering the scathing affects of living so densely together.” One only needed to read the linguistically innovative poetry of Victor Hernandez Cruz, or the traditionally formal poems of Uruyoan Noel, to see that there was no definitive style to Nuyorican poetry. Nevertheless, the aesthetics of the Nuyorican moment were often largely defined by the presence of a Puerto Rican community, one where information was passed from person to person, daily, by word of mouth. But I wasn’t ever a part of that community. I stomped through the creeks of Virginia in winter. I fell in love with the boy across the street, which I couldn’t share with anyone. When I turned to the page, I wasn’t speaking to a community, but to myself as I tried comprehend my own sense of otherness as Latine in a predominantly European-American neighborhood, as a gay young man in a stereotypically homophobic family. When I picked up the pen, the voice I heard was not a shout, but a whisper.

For thirty years, I’ve written, first, poem to poem, and then, book to book, seeking the tools that might best suit the project in front of me, resisting the urge to falling back what comes easiest or what seems most familiar, and instead letting each poem, each book identify its own needs.

As I grow older, beginning my third decade committed to this lifelong passion, I’m still learning, I’m seeking new ways to say whatever I feel compelled to say. Of course, what was important to me when I was 28, wasn’t necessarily what I needed when I was 38, and what I needed ten years ago, isn’t necessarily what I need now. What keeps poetry new and fresh is remaining open to all the models in this ancient art, all the possibilities as we forge our way to say what is important to us in whatever way we have to say it.

Any places to eat or things to do that you can share with our readers? If they have a friend visiting town, what are some spots they could take them to?

For brunch, I love to go to Cara Restaurant in Los Feliz. After eating, you can get a drink and listen to some jazz.

For a casual dinner and drinks, I’ll like Laurel Tavern in Studio City or Idle Hour in North Hollywood.

For a more formal dinner my favorite place to go is Verse in Toluca Lake. The food and drinks are fantastic, the music exceptional.

The Shoutout series is all about recognizing that our success and where we are in life is at least somewhat thanks to the efforts, support, mentorship, love and encouragement of others. So is there someone that you want to dedicate your shoutout to?

I want to dedicate this shoutout to my Puerto Rican grandmother, the first person who spoke to me about poetry, how it could speak for a community or an individual, reflecting a complexity and nuance often lacking in our day-to-day exchanges.

Website: https://Blasfalconer.com

Instagram: Blasfalconer

Twitter: @blas_falconer

Facebook: Blas Falconer

Image Credits

Headshot by Emily Petrie.

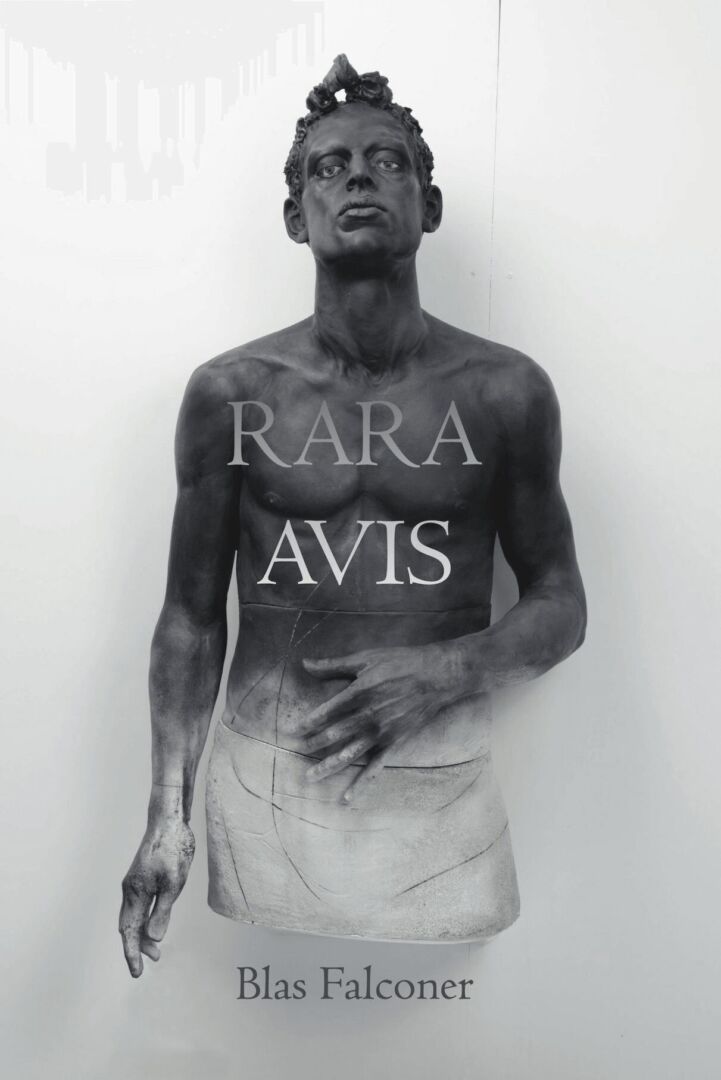

Book cover designed by Ryan Murphy