Meet Yaroslav Golovkin | Cinematographer and filmmaker

We had the good fortune of connecting with Yaroslav Golovkin and we’ve shared our conversation below.

Hi Yaroslav, how do you think about risk?

Speaking about myself has never come naturally, let alone my work — but I found this question about risk surprisingly welcome. I often hear people describe me as a risk-taker nowadays, and I read that as a compliment.

Over the past three years, this word has followed me more than ever, probably because my move to the U.S. was one massive, abrupt risk — one that had to be taken instinctively and without hesitation. And yet, had I not leapt, I wouldn’t have ended up shooting Room Temperature, a feature film by Dennis Cooper and Zac Farley, which just premiered at the wonderful LAFM festival.

Since arriving, risk has become embedded in every layer of life — from logistical basics to moral ambiguities. Reflecting on it, I find that risk animates discovery; it draws us toward the unfamiliar, and that pull might be the closest thing I have to a long-term orientation. Risk in art — at least the kind that veers away from managerial safety — feels essential. Art without risk is dangerously close to commercial territory: a place where one might be “accepted” only to be quietly suffocated by comfort.

These days, I find myself more at peace with art-adjacent commercial structures — maybe because I’ve been exhausted by displacement, by losing a country, a home, and with them, a part of myself. But I still believe that if this world lets you in, you don’t owe it your full obedience. Priorities must remain fluid. I’d rather choose to operate as an avant-garde of the arrière-garde — if I’ll be back to that world ever again.

Of course, not all risk is generative. I believe in rehearsed, calibrated risk — risk that includes space for failure, exploratory terrain, and the occasional strategic bloodletting.

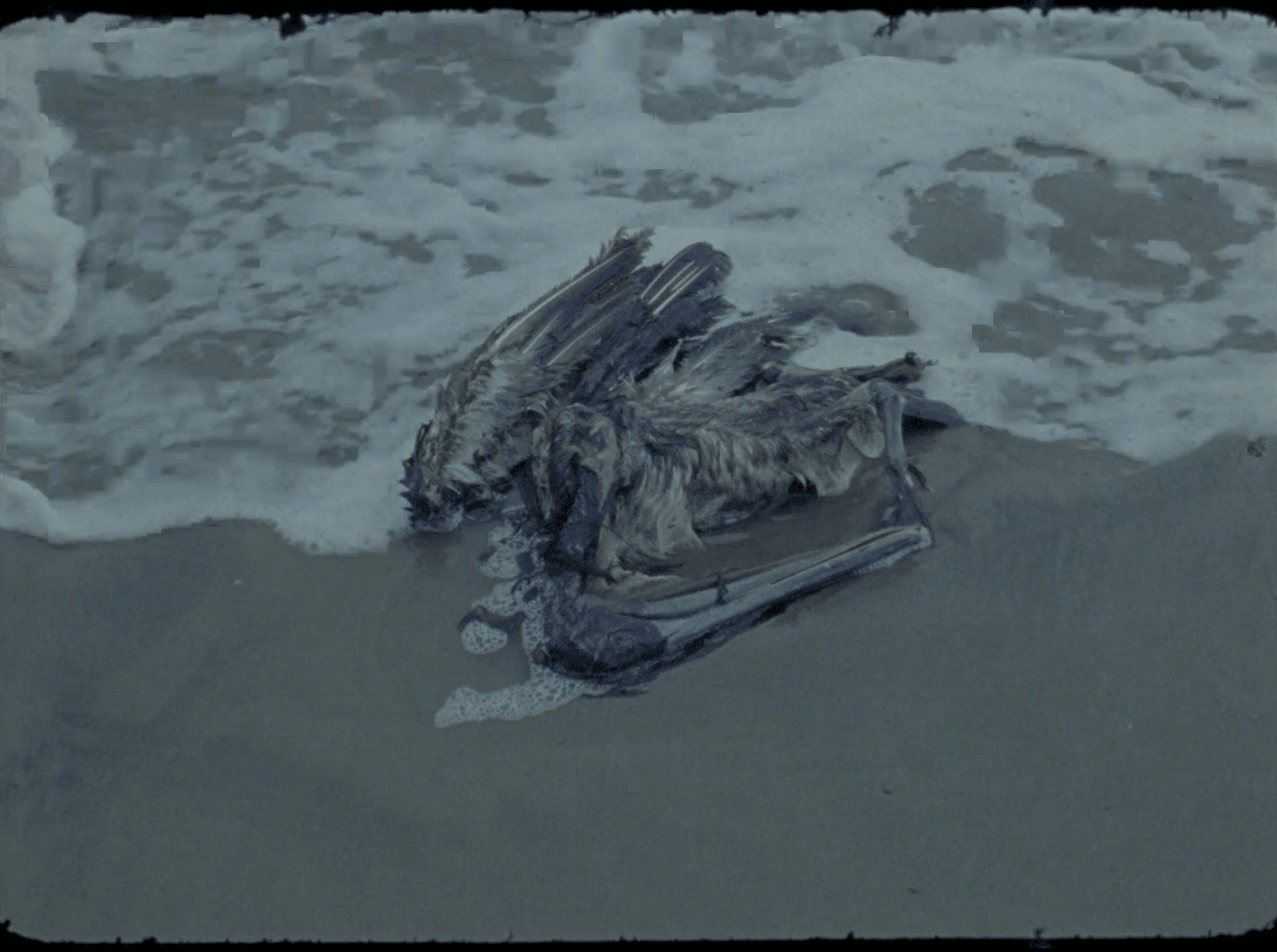

The kind of risk I find most useful in art is the one that disrupts clarity — that breaks apart the illusion of total authorship. If a single mind can completely envision a finished artwork before it’s made, that mind is likely trapped within the conventions of its own imagination. But when plans fail, when the material, the weather, a machine, or an accident interrupts the idea — and we allow those ruptures to remain present within the work — something new can emerge. It’s this friction between intention and the world that receives it that sometimes lifts the work beyond itself. Donna Haraway’s notion of staying with the trouble might describe this best.

On a more practical level, cinematographers are expected to avoid risk. We’re hired precisely because we’re reliable, fluent in the technical, and sensitive to precision. I don’t oppose that — it’s part of the job. But one of my former mentors once suggested that technical mastery is the easy part: learnable, codified, well-practiced. In one lecture, he proposed something more subtle — a deliberate way of inviting disruption into the image. Imagine this: you’re on the tenth take of a handheld scene. You and the director know you already have what you need. But something compels you to keep going — not for safety, but for something more elusive. By now, your body knows the motion. Every rotation of the lens, every step is ingrained. So, for the next take, you switch to a slightly tighter lens. You turn off the monitor. Your hands remember. And something unexpected happens — something the body catches before the eye does. Something slightly less curated, less anthropocentric — more porous to chance. Maybe that’s the best thing you’ll shoot that day.

Let’s talk shop? Tell us more about your career, what can you share with our community?

I work as a cinematographer and will continue to — but I’m also preparing to release several personal, independent projects, and I intend to follow that trajectory as far as it will take me.

I often feel quite separate from most cinematographers in Los Angeles — or simply out of sync with the dominant pedagogies here, which often come through film schools and genre traditions. My own education trained us to work outside of genre, to actively sidestep tropes and resist the established patterns of Western cinematic thinking. I switched between diametrically opposed sets, genres, budgets, values, and methods that cross-pollinate each other. I moved in multiple directions, working with auteurs, contemporary artists, commercial advertisements. In this intentional oscillation, my interest has shifted towards redirecting experience and technology as a resource — from commercial to independent, from exempted to institutionalized, from excessively developed to serendipitous.

As for my personal work, I now find myself sitting on years’ worth of material — filmed in fragmented moments, serendipitously, without a clear plan. Only recently have these fragments begun to converge around shared meanings and form some kind of body — a reflexive structure responding to the environment I grew up in.

One thing I’m quietly proud of is my refusal to work on projects that feel morally or politically dissonant, even when I’ve been in need of work or resources. I’m also proud of specific films — Captive by Lika Nadir, for example, or Room Temperature, which I shot relatively soon after arriving in the U.S. Finding that team reoriented something in me — a reset of creative stamina I hadn’t felt in a while. Before that, my hope to integrate into the local filmmaking ecosystem had nearly faded. Even for someone with a decent body of work, the move can feel like a hard restart. People say if you want to grow fast, stay in one place.

What helped me stay afloat during long stretches of stasis and doubt was a quiet awareness that I still had something to offer. Many of the projects I encountered here didn’t impress me much, and I realized that a more flexible, externally shaped approach might eventually take root — it was just a question of social maneuvering, of navigating trust.

Cinematographers develop a particular kind of intuition — something about being there at the edge of a project’s formation, seeing it halfway into being: during prep, during production, and then again assembled at the offline edit. That temporal rhythm accelerates pattern recognition. You start to feel where things might land. And if you find a true creative ally — a cinematographer whose preferences resonate with yours — this intuition can be a real asset. Of course, most of the insights I developed are fairly practical and unglamorous, but one of the more beautiful things I’ve noticed is this: if you’re working with the right people, the kind you share a perceptual frequency with, certain things just pass between you telepathically. They don’t even have to be said. And there’s nothing better than that.

Let the world know I’m more than ready for the next feature — or a serious and mature short. I’m inclined to commit, and follow it wherever it leads.

Let’s say your best friend was visiting the area and you wanted to show them the best time ever. Where would you take them? Give us a little itinerary – say it was a week long trip, where would you eat, drink, visit, hang out, etc.

Let’s say we arrive in Los Angeles on July 7th — I’ll leave the reason unspoken for now. The day begins with a visit to Forest Lawn Cemetery, which, despite its surreal aesthetics, feels profoundly emblematic of the city. We read the founder’s credo, then make our way up the hill to the Hall of Crucifixion-Resurrection — a structure that feels excessive by design, yet somehow sincere in its conviction. There’s something unexpected waiting at the top, just inside.

Next, we check if Mezzanine has any screenings that day and also stop by the bookstore at Now Instant, which always has something rare. If the mood is right, we visit the Museum of Jurassic Technology and have tea on the rooftop, among the birds that live there — oddly pedigreed creatures that seem to belong to the place more than most people do.

Then we drive to Long Beach, to the Watson area, and find the one spot along the industrial depot where there’s no fence — where you can walk right up to the tracks and wander among the freight and steel. Giant and intricate factories line the industrial perimeter: breathing machines wrapped in glowing tubes, their exhalations catching the light and slicing it into visible shafts as if in a temple, mid-ceremony, dense with labdanum fog.

At midnight, we reach Cabrillo Beach. Something strange begins to happen. The dry sand appears to liquify — not metaphorically, but literally — covered in thousands of shimmering fish moving in rhythmic waves. For a few moments, the beach resembles molten metal, writhing in silver pulses. These are grunion — fish that come ashore once a year to spawn in the sand. They glint under flashlight beams, flipping and burying themselves instinctively, while people crouched in the dark, trying to catch whatever they can.

Just before this begins, you might notice shapes in the water — divers lit up by soft underwater lights. They’re the first sign that something unusual is about to occur, especially at such a late hour.

From the morning in the company of the buried to the urgently living when the sun is down —

all trying, in one way or another, to continue themselves.

Who else deserves some credit and recognition?

I like to think of a single person as an invisible chorus — a voice that carries hundreds of others inside it: friends, mentors, distant inspirations. Each one speaks through us in turn, as if stepping one by one onto the stage of cognition and perception. And many of the names I’m about to mention have, in one way or another, spoken through me — as part of that chorus.

One of the most fortunate elements in my life has been having deeply understanding parents and a grandmother who accept my strangeness and support me despite the distance I’ve put between us. During these last few years of adjusting to Los Angeles, I was held together by the presence of Katya Tomashevskaya — a researcher of visual anthropology and ethnographic media at USC — and by the rare filmmaker and magnanimous soul Rob Rice, who is about to share a very unique film with the world.

Strangely enough, I’m also still sustained by the influence of someone I was once very close to, though we no longer speak. She knows this, and she is somewhere in France.

Everyone involved in the making of Room Temperature was a source of strength. The New Cinema School in Moscow, led by Dmitry Mamuliya, left a lasting imprint on my preferences in film. Even earlier, MIFS — my first film school — still echoes in my mind through the voices of its mentors.

Organizations like OVD-Info and Memorial continue to move me — their very existence feels necessary as they support political prisoners and detainees. They deserve all the visibility and support they can get.

In recent years, the writings of Loretta Fahrenholz, Peter Gelderloos, Mircea Cărtărescu, Timothy Morton, and Ernst Jünger have quietly eased the rougher parts of adapting to this place.

It would be difficult to stop listing the filmmakers who’ve left a mark, but here is a partial constellation: Fern Silva, Dana Kavelina, Tsai Ming-liang, Nastia Korkia, Hu Bo, Vika Kirchenbauer, Eduardo Williams, Maria Ignatenko, Philippe Grandrieux, Emilija Škarnulytė, Carlos Casas, Katia Selenkina, early Apichatpong, Natalya Meshchaninova, Christi Puiu, Maria Speth, Sergey Dvortsevoy, Hannah Hummel, Christian Petzold, Deborah Stratman, Ana Vaz, Ulrich Seidl, Marianne Pistone, Roy Andersson, Jessica Sarah Rinland, Virgil Vernier, Véréna Paravel, and Lucien Castaing-Taylor.

Website: https://vimeo.com/user9101650

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/yyy_rrr_ccc/

Twitter: https://www.threads.com/@yyy_rrr_ccc

Soundcloud: https://soundcloud.com/peskobeton

Other: https://catalyzm.com/directors/golovkin

https://catalyzm.com/cinematographers/golovkin

Image Credits

Rob Rice

Guanyizhuo Yao

Yaroslav Golovkin