Meet Zhi Qu | Stage Director, Actor, and Singer

We had the good fortune of connecting with Zhi Qu and we’ve shared our conversation below.

Hi Zhi, what led you to pursuing a creative path professionally?

Unlike many people around me, I didn’t decide to pursue the arts—or choose theatre as my future career—until after completing my first year of graduate school. Before that, I was constantly drifting between different fields, unable to make any firm decisions. I suppose it was either because I hadn’t yet found something I truly loved, or because I wasn’t ready to admit what I loved.

Since my freshman year in college, I have been involved in the Chinese drama society as an actor. Over four years, I performed in more than ten roles and had the honor of co-directing two classic plays. That experience planted the first seed of passion in me. Later, my choice of a new academic path brought me to New York. Outside of my studies, I began auditioning for various Chinese and English-language plays and musicals. Through these productions, I met many talented peers who shared the same passion and dedication. In April 2023, shortly after the curtain fell on The Hanging Garden Murder Case, a Chinese rock musical in which I played the lead, I entered my first summer break as a graduate student. It was during that time of reflection that I finally understood: I wanted to exist in this world as an artist. Theatre, music, and the arts—these are the things I truly love, and the things I wish to pursue as a lifelong career.

Since then, I’ve intentionally sought out more artistic opportunities and taken on a wider range of roles—from actor to director, from vocalist to artistic director. Eventually, I chose directing as my main professional focus, though I’ve never turned down chances to perform or sing on stage. That’s because, compared to acting, directing allows me to express a more complete and integrated artistic vision. At the same time, staying involved as an actor keeps me grounded in the performer’s experience, and working under different directors helps me learn new approaches and open new perspectives.

So far, this dual identity has been incredibly rewarding. For example, in our recent bilingual original play Anti-Gone: 俺抬杠?!, I played two characters: Haimon and the Eunuch. During one rehearsal, I realized first-hand as an actor how easy it is to accidentally hurt a scene partner when overly immersed in a role—a nuance I had overlooked or even encouraged in the past when directing. On the flip side, my directing experience informs my acting choices: I think about spatial awareness, rhythm, and energy balance with my scene partners; I also consider how much improvisation I should allow myself without disrupting the overall coherence of the scene. These two perspectives enrich each other and help me grow both as an artist and as a storyteller.

So, back to the original question—why do I want to pursue a creative or artistic career? At its core, I think it’s because I have a deep urge to express. I have my own thoughts and judgments about the world, about social issues, human relationships, and systems of values—many of which might differ from the mainstream. This way of thinking probably stems from my academic background in sociology and philosophy.

And why theatre, specifically? I find it fascinating that theatre allows us to speak in a roundabout way. In real life, if you speak too bluntly, you can alienate people. But if you’re too vague, you risk being dismissed as confusing or insincere. Most everyday conversations fall into that middle space—safe, dull, and emotionally distant. But in the theatre, everyone knows it’s a play. It’s not real. And because of that, allegorical or symbolic expression becomes more acceptable, even welcome. A thousand people can interpret Hamlet in a thousand different ways—and somehow, your true thoughts can come through more clearly when wrapped in metaphor.

Beyond expression, I also resonate deeply with something a distinguished opera director once said: Artists create because they don’t believe in the world they see. By that definition, perhaps everyone is born an artist. We all perceive the world differently, but the artist’s task is to find a way to express those perceptions. As someone who may not be the most skilled, but certainly loves to speak and express, I truly believe that making art is the work I’m meant to do.

Let’s talk shop? Tell us more about your career, what can you share with our community?

Hi guys! It’s so exciting to meet you. My name is Zhi Qu. I was born in Beijing, China, and am now based in New York City. I am a director with works spanning theater, dance, opera, concerts, and large-scale galas. I also work as an actor and a singer in different off-off-Broadway and off-Broadway productions.

As a theater director, the heart of my work lies in breaking the boundaries of language through cross-cultural means—integrating elements from traditional Chinese opera, physical theater, classical music, and devising & improvising practices. I emphasize musicality, rhythm, and dramatic tension in the theatrical space, while reimagining and expressing stories through a collective, people-centered historical lens.

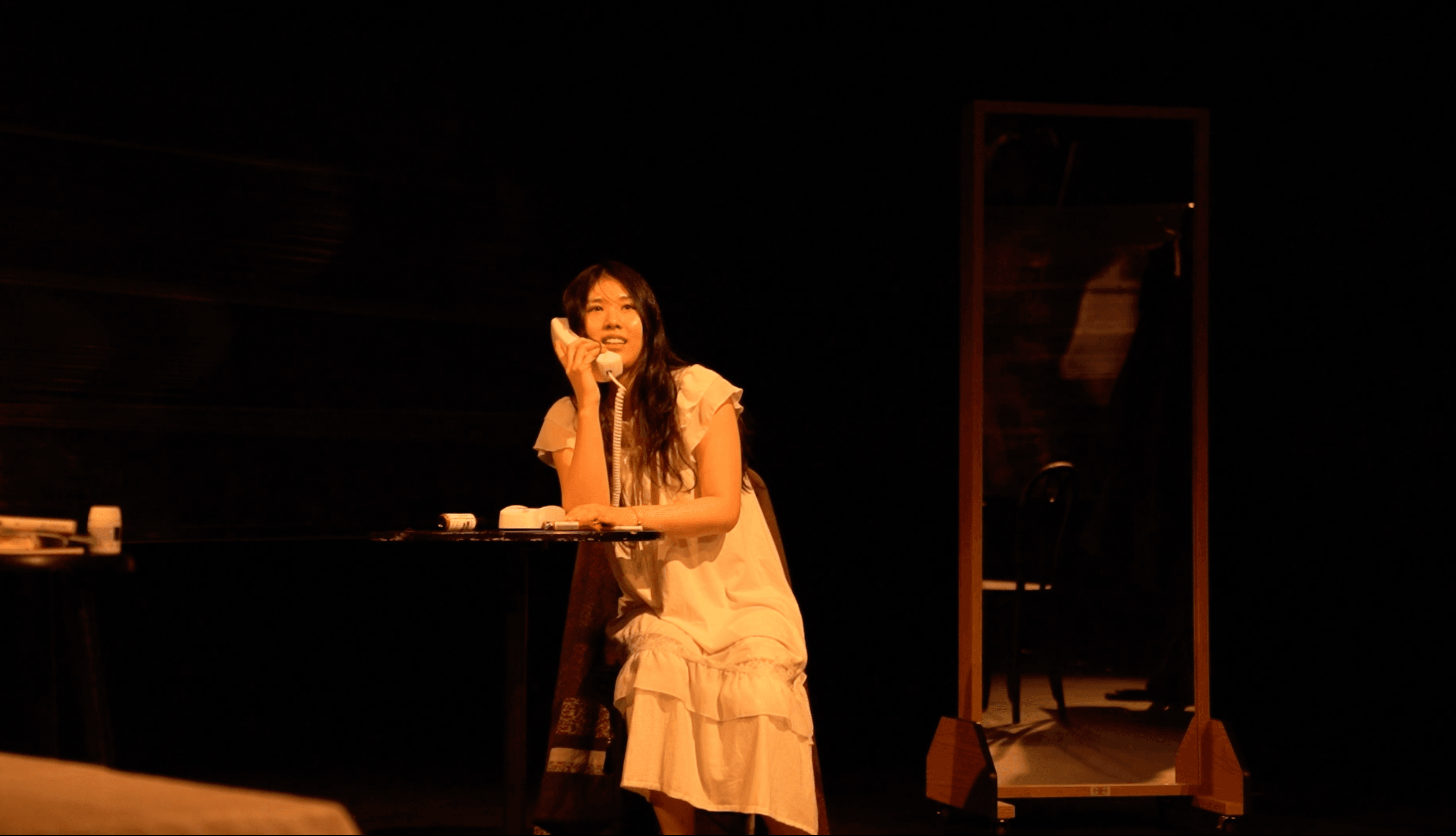

Through my journey as a director, Language has always been a central theme in my artistic exploration. I am constantly drawn to the abstraction and redefinition of language—examining how the deliberate dismantling of linguistic barriers can open up new modes of storytelling that better reflect contemporary social life and issues. My work often incorporates non-verbal elements such as various design elements and an emphasis on the physical and vocal presence of the actors. In my short dance & physical theater piece Love Between a Bird and a Fish, for instance, I used the symbolic imagery of a “bird” and a “fish” to explore the push and pull, the struggle, and the suffocation that can exist within intimacy—without the use of spoken dialogue. And in my avant-garde monodrama La Voix Humaine, performed in Shanghainese, I stripped language of its informational function entirely, allowing it to serve purely as a personified vocal medium for raw emotional expression.

In most of my works, I seek the edges of language and experiment with theatrical forms beyond realism and naturalism, integrating new technologies and emerging ideologies into my practice. For I believe the director’s task is to create a fourth dimension within the three-dimensional space of the stage. This also speaks to what sets my work apart: it is often inspired by the Chinese aesthetic philosophy of Yijing (意境)—a poetic sense of atmosphere and meaning beyond words. Whether in visual presentation or conceptual interpretation, I strive to create a space that cannot be fully articulated, but can be intuitively felt. Rather than asking the audience to process meaning solely through language, I aim to evoke emotion and atmosphere through non-verbal expression. Language is limited in what it can convey; it is often what lies beneath and beyond language that is more intricate—and more essential.

One of my most recent projects was serving as the chief director of NYU GALA 2025 – A Journey to the West, a large-scale performance co-produced with Hunan TV International and staged at the historic Apollo Theater. Unlike most traditional GALA formats, I took an innovative approach by constructing a dramatic narrative arc that connected 31 various programs—spanning music, dance, drama, animation, and film—into a cohesive theatrical experience. The story follows a Chinese international student’s journey from Shanghai to New York, where he navigates challenges, encounters growth, and ultimately finds his unique pursuit. This was a large-scale production, involving nearly 300 performers and crew members. It also gave me the opportunity to fully exercise another strength of mine as a director: applying principles of arts management to lead the early stages of planning and coordination, collaborating closely with production teams to ensure effective execution, and maintaining open, collaborative communication with performers, program leads, and designers across all segments of the show. Thanks to this integrated approach, the production advanced with clarity, efficiency, and a shared creative spirit across departments. In addition, I firmly believe that this hybrid form initiated by me represents a future direction for GALA-style events: one that preserves the richness of multiple artistic expressions while offering the emotional consistency and layered meaning that only theatrical storytelling can provide.

Beyond my ongoing exploration of the boundaries of language in theater, another recurring theme that runs through all my work is departure (出走). Many of my directing projects revolve around examining the act of departing—its definitions, motivations, and consequences. What draws me so deeply to this theme is the fact that I see myself as someone constantly in departure. Seven years ago, I made the decision to move to the other side of the world to study and live. Three years ago, I picked a different path for graduate school. And two years ago, I made perhaps the most defining decision of my life thus far: to choose theater and directing as my career. I’ve been stepping out of my comfort zone ever since, in pursuit of what truly calls to me. To me, departure often stems from a sense that one’s current environment no longer fulfills their desires or pursuits, or perhaps one chooses to leave simply because he/she can no longer bear the weight of their present situation. However, once the decision to leave is made, it often leads not to arrival, but to another kind of limbo—a cycle of staying and departures. In this sense, every entrance is born of an exit, and every exit, in turn, marks the beginning of a new entrance. In my previous works, I’ve consistently explored the duality of departure. In the final moment of La Voix Humaine, the woman tears the telephone cord twining her neck and exits the theater through the audience, while whispering “I love you.” This act can be interpreted both as her death and as a moment of the liberation of herself—a symbolic departure from the emotional entanglement that has haunted her consistently. In Remorse, during the fourth act, the protagonist Zi Jun walks away from the home she had built with her lover, Juansheng, as the opera’s main theme “Wisteria,” swells into a full chorus. In the original novel, Zijun dies after departing. But in my vision, a beam of intense warm light facing her from downstage evokes the sensation of a hopeful dawn—strikingly contrasted with the heavy, somber tone of the act—suggesting that she has finally reclaimed her autonomy.

These previous works inspired me to further expand my inquiry into departure by focusing on women across different times and cultures: a young girl from the Tang dynasty, fifteen centuries ago, and a middle-aged British woman from the early 20th century. What drives them to depart? What parallels and divergences shape their journey of departure? I look forward to deepening this exploration in my upcoming productions, where their stories will unfold on stage—not as isolated narratives, but as reflections of a shared human longing for selfhood, pursuit, and change.

Any places to eat or things to do that you can share with our readers? If they have a friend visiting town, what are some spots they could take them to?

Absolutely! A bunch of ideas just jumped into my head.

First, I’d take my friends to try some authentic Italian food—places like Il Corso on 46th Street and Fifth Avenue, or IT Italian Trattoria near Times Square. Of course, Chinese, Japanese, Thai, and Malaysian cuisines are also great options. Personally, I love Soothr, a Thai restaurant on East 13th Street, and West New Malaysia in Chinatown. I go to both of them several times a month—they’re just that good.

As for drinks, New York is packed with amazing specialty coffee shops. My go-to spots are Moshava Coffee, a cozy Jewish café right by Washington Square Park, and Puerto Rico Importing Co., tucked next to West Village. Both places share a few things in common: friendly service, peaceful vibes, and excellent coffee at unbelievably low prices (a latte for just $4!). Another favorite of mine is Hi-Collar in East Village—a Japanese coffee shop by day that transforms into a whiskey and cocktail bar at night.

After a good meal, we’d take a walk—either around Washington Square Park or Central Park. Along the way, we might pass by some of the big NYC landmarks like the Broadway theater district, the Empire State Building, or Rockefeller Plaza—passing by is just fine, no need to get in. Instead, I’d rather shift our focus to the lesser-known gems—those tucked-away record stores on street corners or in basements: 54 Vintage Vinyl, Academy Records, Generation Records… Each of them has its own unique curation and personality. And the best part? You can find rare vintage records, especially opera and classical albums, at super reasonable prices.

To wrap up the night—yes, beyond hitting a bar or two—I’d say the must-do is to catch a performance at one of New York’s off-Broadway or small theatres. Trust me: more than all the glitzy, multimillion-dollar Broadway blockbusters, it’s the small shows and showcases in black box spaces that hold the true soul of New York theatre.

The Shoutout series is all about recognizing that our success and where we are in life is at least somewhat thanks to the efforts, support, mentorship, love and encouragement of others. So is there someone that you want to dedicate your shoutout to?

Absolutely—there are many people and things that have helped me, inspired me, and pushed me forward on my journey in theatre and the arts. But if I had to dedicate my shoutout, it would go to two people and one organization.

The organization is the UCSB Babanana Chinese Theater Club, which I joined during undergrad. I’ve already mentioned it before, but it really deserves the spotlight. Looking back now, those years were anything but “professional” in the conventional sense—we rehearsed in empty classrooms with no formal stage structure, no stage manager, no lighting designer. On performance nights, there was no lighting cue system, and our costumes were literally assembled from whatever we could find in our closets—people just picked the best-looking outfit they had and wore it on stage. Among the dozens of us, maybe only one or two were actually theatre majors. And yet, those years remain some of the most magical and important ones in my artistic life. That “unprofessionalism” gave us something raw and beautiful—a space full of love, passion, and equality. Everyone was welcomed, everyone contributed, and everyone treated each other like family. That environment protected the spark of my love for theatre when it was still fragile. The more I’ve experienced in more formal or professional settings, the more I miss those late nights rehearsing in our little coastal college town. That time not only nurtured my passion but also shaped how I approach collaboration and the rehearsal room—it taught me to keep theatre playful, collective, and full of heart.

As for the two people I want to thank, the first is my godfather, Mr. Dai Yuqiang. He’s one of the most accomplished and well-known operatic tenors in China. I grew up listening to his recordings and watching his performances. Later, starting in my junior year of college, I began formally studying bel canto with him. His artistic standards, the rich color and emotion in his voice, and the way he approaches stage performance left a huge impression on me. He set a living example of artistic pursuit—not only in technique but in soul. His mentorship shaped my aesthetic judgment and helped me develop my own sense of musical and dramatic taste. I still genuinely believe he is the greatest Calaf in Turandot that the world has seen.

The second is the opera director Mr. Li Wei, who introduced me to the world of directing. I first encountered his work through an article he had written, and I was immediately struck by the combination of wild imagination and precise, logical thinking. In the summer of 2023, I had the honor of meeting him in person and serving as his temporary assistant director. Watching how he moved in the rehearsal room, observing every choice he made, and chatting with him about art and life—all of that influenced me deeply. After returning to the U.S., I finally made up my mind to seriously try directing. I started taking directing classes and began taking on directing roles in independent projects to gain hands-on experience. Eventually, in early 2025, I made my debut as both director and artistic director with the Chinese opera Remorse, staged at Dixon Place, one of New York’s iconic Off-Broadway venues.

Beyond their artistic influence, these mentors and experiences taught me how to enter this industry, and here, my views might be a bit unconventional. As both a director and actor, I don’t fully agree with the idea that one must get a degree in theatre or take dozens of structured courses before being “ready.” We live in a time of information abundance. The digital age and globalization have given us nearly unlimited access to knowledge. Unless there’s a total content revolution around the corner, most of what’s taught in conservatories stays relatively fixed. Theatre directing, unlike physics or vocal technique, doesn’t always require a rigid, intergenerational, data-heavy methodology. It grows through practice—through collaboration with artists from different walks of life, through trial and error, through listening and adjusting.

Of course, I’m not saying theory doesn’t matter. On the contrary, I think methodological literacy is one of the most important pillars for a director’s long-term growth. But as the old Chinese saying goes, “To believe every word in a book is worse than reading no books at all.” In my time working in New York, I’ve seen how some people become obsessed with degrees and textbooks. They end up creating privileged cliques in the rehearsal room—consciously or not—excluding those without formal academic backgrounds. That kind of arrogance and gatekeeping is exactly what I resist and avoid. From my own journey, I can say this: most of the inspirations that truly shaped my artistic lens—those that I actively apply to my work—don’t actually come from theatre training. They come from classical music, literature, poetry, cinema, and visual art. Every director interprets the world differently. The same sentence might evoke a poem for one, and a musical composition for another. That difference, that plurality, is the best thing about being human. In the rehearsal room, what matters most is not how you think, but how you communicate and how you express it to others.

So here’s my real message: not having a formal degree or enough knowledge should never be a reason not to start. If you love theatre—if you’re passionate and feel called to make something—start. Start now. Take the first step, meet people who resonate with you, and grow along the way. Don’t let your lack of credentials make you feel ashamed or inferior. Your unique background might be exactly what someone else finds refreshing and inspiring. And don’t forget—you have access to more resources than ever before. Books, videos, online courses, crash programs, communities… You can absolutely self-educate at a high level. If you want to do it, and you feel you have to do it, then do it. Don’t overthink. Just begin. Don’t disqualify yourself too soon. Hold onto that fire, even if some people call it naive or reckless.

Whenever I fall into doubt or anxiety, I think of that moment in Forrest Gump—when Jenny yells, “Run, Forrest, run!” Forrest breaks free of his leg braces and runs—and he keeps running, until he crosses the whole country. How he became famous, how he made money, how he became a household name—it all happened along the way. So please forget “Where should I go?” or “What’s up ahead?” for now. Just run. The road will appear beneath your feet.

Website: https://zhiqu.art

Instagram: @frankqz0703

Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/in/zhi-qu-a43754276/