Meet Colm Summers | Theatre Director

We had the good fortune of connecting with Colm Summers and we’ve shared our conversation below.

Hi Colm, how do you think about risk?

Life in the arts – and in particular life in the theatre – is perilous. Risk abounds. Everywhere, theatre artists live and work at the limits of financial precarity and career stability. For most theatre professionals, the phrase “work-life balance” is almost laughable. In the time of Covid-19, the health risk of gathering has further compounded the problem, as audiences hesitate to gather together and breathe the same air.

From the point of view of career, there has never – in living memory – been a “riskier” time to be a theatre artist. At the same time, risk is inherent in our creative process. We do it live! Anything could happen, and every choice we make in the creative process needs to be calibrated with that risk in mind. Often, the moments of live performance which linger longest in the minds of the audience are the decisions which felt most “risky” to the creative team. No one in the audience remembers the “safe” choices. In our artform, risk is a key ingredient in making lasting memories.

Sometimes the instability inherent in a theatre career can negatively impact our ability – as artists – to make those risky decisions. It’s difficult to make vulnerable or ambitious creative choices when you’re dealing with a scarcity of resources. You might not, in a reduced rehearsal process, for example, plan that ambitious choreography sequence, because of the limitations you face in the time given to you. You might not, as an emerging artist, be paid enough to prepare to your full potential, because you’re forced to take multiple jobs to make ends meet. As a risk averse industry reacts to dwindling audience numbers, the opportunities afforded to risk-taking artists dwindle too.

Something I think about a lot is how the industry labor standards directly affect the work we are able to make. Theatre is an artform for risk-takers; it’s essential the theatre industry engenders working environments where creative “risk-taking” remains possible. In my work, risk-taking is essential – I cherish it – and all artists deserve a culture-industry willing to support our risk-taking fully.

Can you open up a bit about your work and career? We’re big fans and we’d love for our community to learn more about your work.

My parents, both investigative journalists, moved us from Washington D.C., to rural Ireland when I was a child. Growing up there – an accented American and a nascent queer in a Gaelic-speaking area of southernmost, rural Ireland – has given me a lasting sympathy for outsiders, and a deep respect for community. In theatre, I found, and formed, the community I craved.

As a director, I carry my parents’ determination to speak truth to power, and the instinct to listen, with me in my work: I make choices which honor the role of theatre as a kind of emotional journalism, and create a space for outsiders to tell their story. When I approach a text, be it a new or classical play, I ask the question, “whose voice here goes unheard?”

The theatre, from my point of view, is therefore fundamentally a way of creating space and time for a diversity of thinking and feeling – an “Other” place, where anything is possible. My belief in the theatre as a utopia in which to invent new ways of being has shaped my work as a director. I feel most creatively fulfilled by theatre that is character-driven, anthemic, bittersweet and dares us to believe in magic.

I’m excited to tackle a show that meets these high expectations of theatre in the amazing work of my close collaborator, playwright A.A. Brenner, who’s new play “Blanche & Stella” exists at the intersection of queerness, disability and belonging. It open in May 2022, in New York City.

As a generative director, the themes I have addressed are central to my new play “When David Buckel Saved the World,” about the climate activist David Buckel, created with his widow, Terry Kaelber over the course of the last three years. The play posits an alternative history of the future, in which we resolve the climate crisis. The piece will be presented as a work-in-progress this summer at the Gate Theatre in Dublin, Ireland.

If you had a friend visiting you, what are some of the local spots you’d want to take them around to?

If it’s a weekend in New York, then I say Friday we start with Barbès in Brooklyn for music – any music at Barbès! The next morning, we would hit the Met Museum Cloisters uptown for an art adventure, then drift down to Tompkins Square Park to linger in the sun and watch the world go by – likely with a Sunny and Annie’s Deli sandwich in hand. Delicious.

For drinks, it’s the 11th St. Bar, a home away from home for the Irish and the best Guinness in town. Sunday morning, get up late and hit one of the green spaces, Prospect Park is my go-to! From there it’s the Brooklyn Museum, or just roving from used bookshop to used bookshop, (that, or antiquing in Gramercy)! Finish up in Manhattan, watching the sun set with a long drink on one of the piers downtown.

Shoutout is all about shouting out others who you feel deserve additional recognition and exposure. Who would you like to shoutout?

One of the most meaningful facets of the theatre is how community leaps up around productions, and how production histories and programmes (the lists of collaborators involved in those shows) form family trees that link these communities over years, decades, (even centuries!) and across continents. I’ve often daydreamed about a “family tree” of collaborators and mentors that we could trace back to the beginning. So-and-so was in this play at this time in this place, and so-and-so was trained by so-and-so, who originated the role, and so-and-so designed this costume for them at this time, and that costume was worn again in this other show a decade later, and so on.

So, I’d like to shoutout the people who pass on this community knowledge: the secret history of the theatre. The costume designer who sewed the name of such-and-such an actor onto the original costume, only to be found years later when the role is played again by some student in drama school. The stage managers who fastidiously kept the blocking notes for productions, with no guarantee they would ever be staged again. The institutional archivist meticulously indexing production photography for posterity. The teachers and mentors who shared half-remembered lessons from their teachers and mentors, so that over generations of teaching – like a game of theatrical telephone – the teachings are passed down to new students, who in turn half-remember them and pass the lesson on.

I’d like to directly shoutout my mentors, Anne Bogart, Katie Mitchell, Brian Kulick, and Nicholas Johnson, who introduced me to the secret history. I’d like to conclude by acknowledging the invisible support and effort of those behind the scenes in my own career, from my colleague Emma Denson – from whom I learn so much – to my mother, Robbyn, from whom I have stolen every good idea I ever had.

Website: www.colmsummers.com

Instagram: @colm_summers

Image Credits

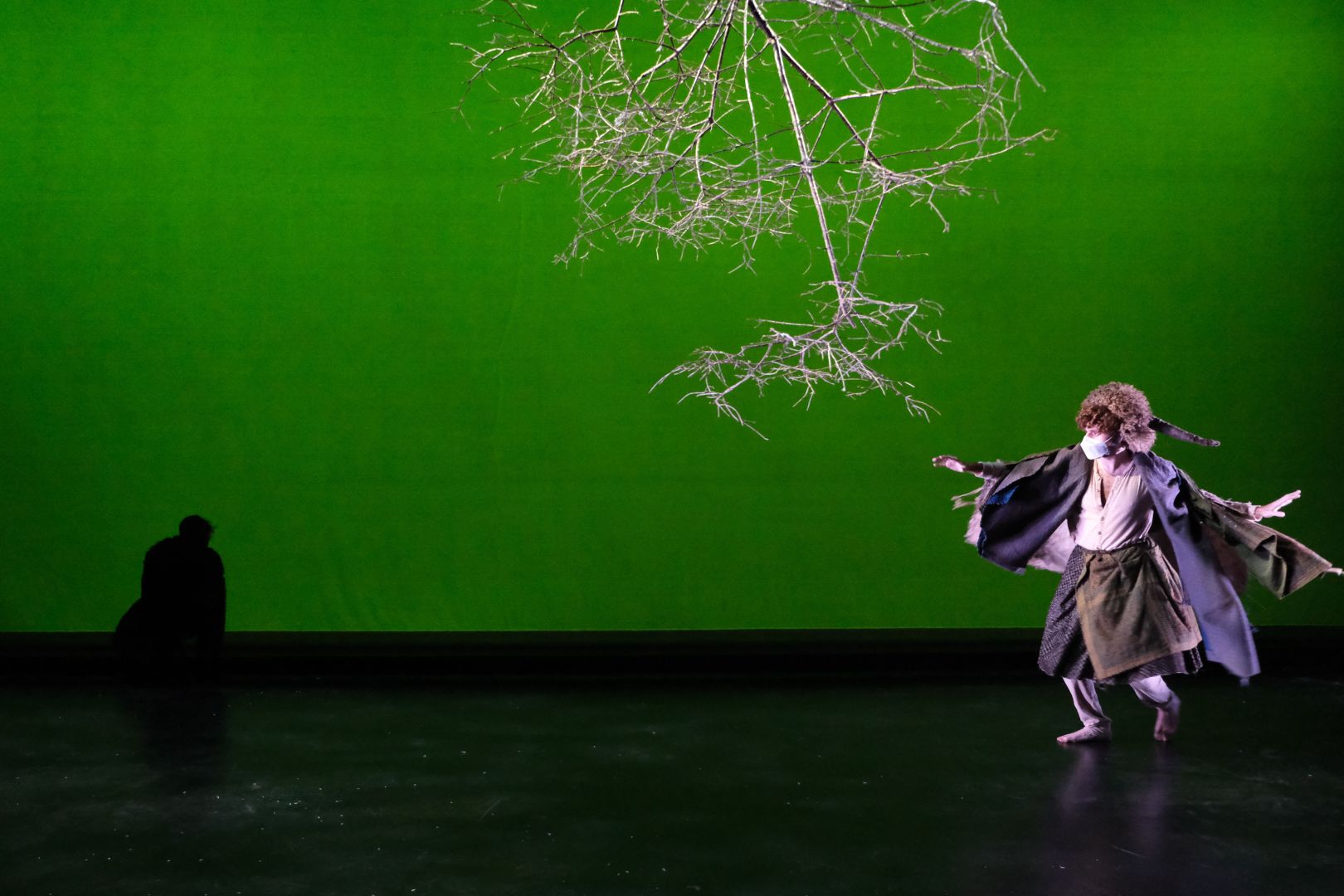

Image 1: by Evan Anderson Image 5: by Evan Anderson All other imagery owned by the artist.