Meet Juan Delgado | A poet = one who makes or shapes

We had the good fortune of connecting with Juan Delgado and we’ve shared our conversation below.

Hi Juan, what led you to pursuing a creative path professionally?

To write about what enables us to develop into artists and have creative practices is a construction, a kind of fiction. At first glance, I could mention the belief that we have uniqueness as individuals and that we have gifts, special skills and talents, and that we should respect those “gifts” by working hard in shaping them. But as a kid, I didn’t see myself as “special” or having natural talents or even being touched by the hand of God to be a painter or poet. Growing up in Mexico and crossing the border into the US and living in a number of cities in Southern California, I was aware of our nomadic way of life, traveling in buses, trains, and cars across countries, staying in makeshift houses, going into classrooms where few spoke my first language, Spanish. Being the new kid in the classroom or in the neighborhood enabled me to ask a simple question: “How is it I find myself here?” By asking this question, I took a step back from my daily world, knowing our family circumstances could change if our father didn’t find a job. Change was a normal part of our lives, but it was the rate of change that could be bewildering. One month we could be driving into LA and be overwhelmed by the freeway architectural structures, the way it veered and bridged into the sky, then merged back into another highway. We could also find ourselves walking a cobblestone street in the heart of Guadalajara. Taking notes about these kinds of shifts and changes made me find a personal language within art that enabled me to better understand the question: “How do we find ourselves here?” Over the years describing “here” in poems and artwork and exploring its connections and incongruities led me to cultivate my art.

Let’s talk shop? Tell us more about your career, what can you share with our community?

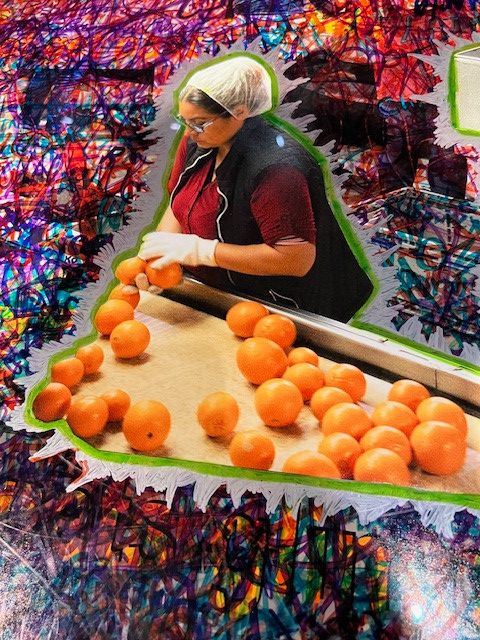

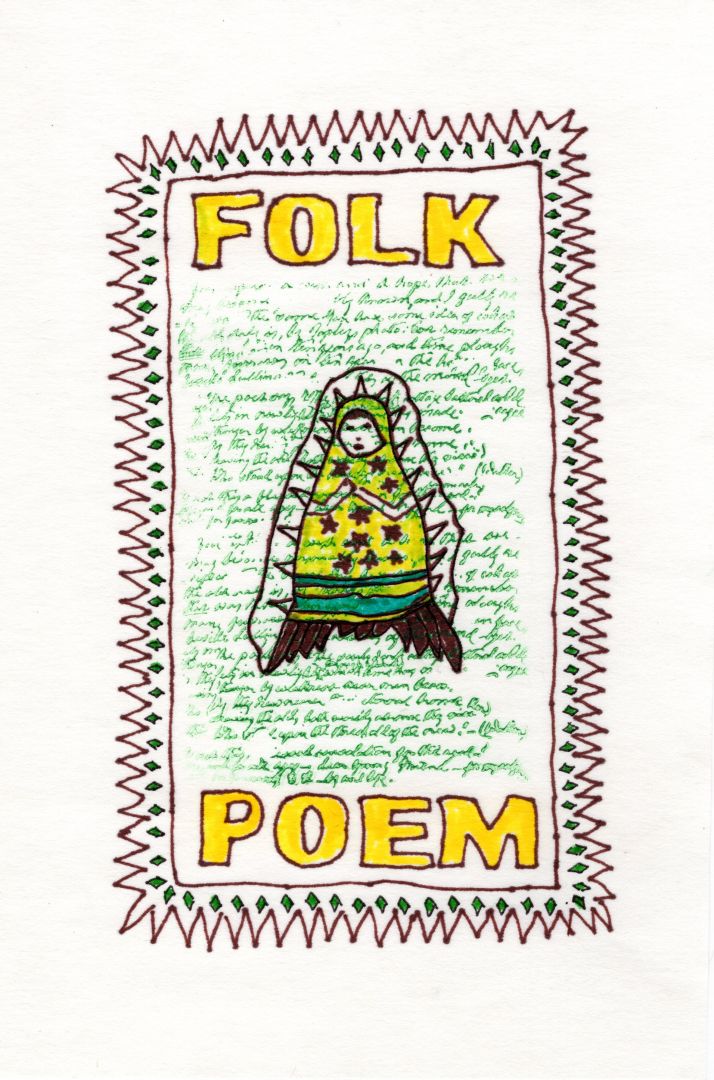

Too much of my formal schooling narrowed the areas of knowledge into 18th-century understandings of fields of study and fostered hierarchies and academic binaries. So, I learned the art of acquiring knowledge outside the classroom and breaking away from my formal education. For instance, I studied Paul Klee’s On Modern Art and Francisco Goya’s Los Caprichos while I created images with poetic captions. As you can imagine, I am a fan of artists like William Blake, who is an accomplished poet and painter. So, working with a painter and photographer was natural and allowed me to learn how creativity can be a collaborative process, a process where meaning is constructed within a partnership and where learning is a team effort. I am moving away from the concept of individual based art production, and I am working with friends to create art projects that feature our local communities. For instance, photographer Tom McGovern and I displayed artwork in abandoned store front windows in our city of San Bernardino. We also exhibited several installations dealing with the local citrus industry, focusing on the pickers in groves and women working in packing houses.

So, I am interested in how poetic work can jump off the 8″ by 11″ page. That’s why I am interested in concrete poetry, a fusion of several art traditions. As I get older, I am less and less worried about the labels they place on us. I think of poets like John Clare who was labelled a “peasant” poet, but whose descriptions of nightingales go beyond the scope and intelligence of his more “learned” contemporaries. He was another poet who dealt with poverty and mental issues, being institutionalized for a substantial part of his life. John Clare was a self-taught poet, and reading was probably the most important learning activity besides his long nature walks. He is the “badger” being besieged due to his personal eccentricities and strangeness of thought. Reading must have been a taxing experience, given his circumstances. I am sure that reading was not something Clare took for granted. I believe that critical reading is not just a practice of surviving but of thriving. I read writers such as Richard Wright who dramatize how reading is a practice for risk-taking, endurance, tolerance, and resistance. As for advice, I say invest a great deal of time and effort in understanding and enriching yourself as a reader of literature or a viewer of artwork. Interpreting a story or painting is a spirited process that stimulates growth.

If you had a friend visiting you, what are some of the local spots you’d want to take them around to?

I would take my friend to El Monte, drive around the city to stop at thrift stores and search for nothing in particular. Junk stores have wonderful names such as “Savers” and “dd’s Discount.” Going into a thrift store anywhere in Southern California is a journey of unearthing–I never know what I will find. When I shop at a thrift store, I often find some item that I didn’t expect to buy. I would walk around the clothing racks and aisles, asking myself: Do I really need a cigar box full of stamps, a pair of boxing gloves, or a watercolor painting of a Japanese geisha? After shopping, my friend and I would show off our best bargains, displaying our knowledge of vintage glassware and vinyl records. I would fan the air in triumph with my newly found record of The Weavers.

Like me, my best friend would greatly appreciate the importance of supporting one’s local junk stores. Some of the best stores have everything one would need to start up a household. As a kid, our family depended on a good thrift store for school clothing, kitchen tables, baby strollers, garden tools, and of course, toys. It’s not just about recycling clothing or pots and pans; it’s about giving new biographies to someone else’s heirlooms. My friend and I would talk about the joy of giving a present-day narrative to a decorative lamp or a set of earrings. Restoring a cast iron skillet or a poker table is the beginning of that object’s new life. Over a beer, we would imagine the past lives of our bought objects, independent of us. We would ask each other: “Which one of your objects will acquire a new biography after you’re gone?” There is less and less fear behind this question, accepting that the objects we bought are more than their individual parts and past lives. We would laugh the evening away, both of us trying to peel off the green price tags from our treasures.

The Shoutout series is all about recognizing that our success and where we are in life is at least somewhat thanks to the efforts, support, mentorship, love and encouragement of others. So is there someone that you want to dedicate your shoutout to?

When it comes to wolves and coyotes there is an important distinction between running in a pack or a family. When it comes to being a professional artist and poet, I belong to a pack of artistic and literary friends and mentors. For sure, I run in a pack that is interested in artistic, political, social and cultural movements; I run in a pack of extremely talented teachers who gave me the license to carry on and run alongside them. I also have a wonderful network of collaborators who have enriched my life with meaningful conversations about living our lives as artists. This last pack is held together by our shared experiences and values, a kind of pack that cuts across geographical locations and specific periods in my artistic development. The conversations we have might first seem like dialogues about poetry, photography, and art production, but they are more importantly about walking together, shoulder to shoulder, over long distances and through emotionally challenging landscapes. These conversations are examples of how we think within our pack, a complex set of networks where politics, art, science, and history co-exist. I am pale without my pack of collaborators: Thomas McGovern (photographer), Simon Silva (painter), Larry Kramer (poet), and others.

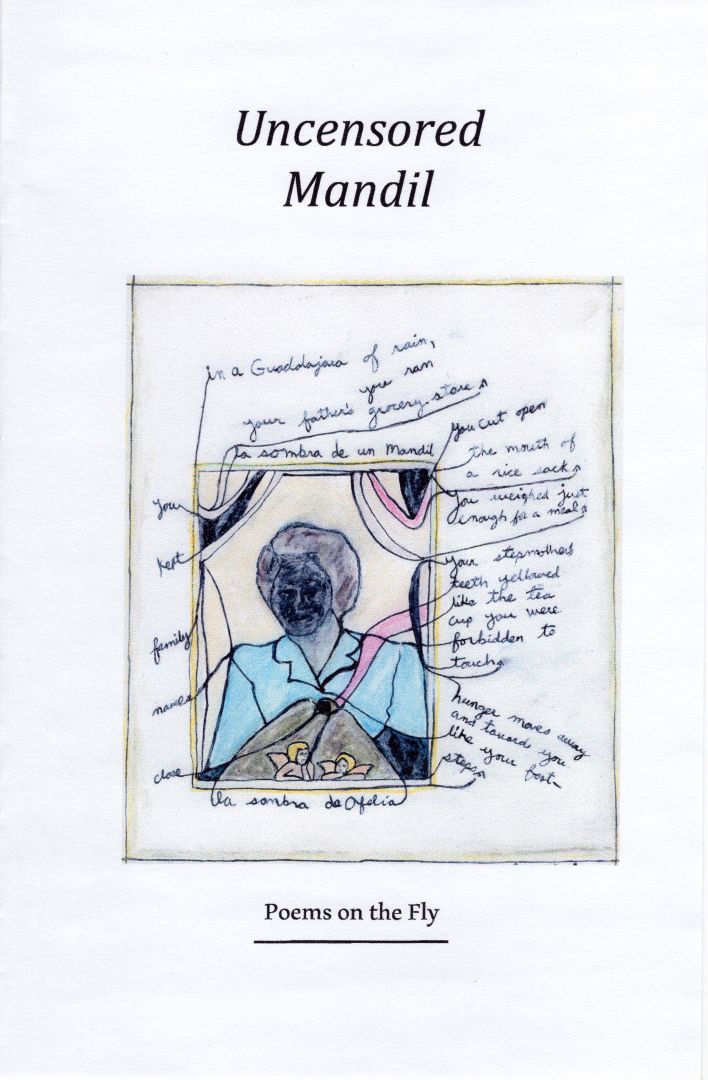

But I also want to give a shoutout to Ofelia Camacho Delgado and Juan Muro Delgado, my parents. Before officially joining a pack, I was part of a close family unit–three sisters and a little brother. My mother’s Catholic faith was instrumental in my maturity as a thinker and understanding the complexities affecting our lives. Attending church with my mother was my first museum experience, taking in all those paintings and statues, experiencing the theater of the mass, and reciting biblical verse. I studied the bodies in front of me, focusing on their anatomical parts, asking why the palms of their hands were turned upward. I considered the metaphorical implications of how these bodies where positioned, displayed, and distorted. The stories of these biblical figures went beyond the sermons of our local priests. There was a mystery in their body language that kept me fixed in my pew. My father embodied another kind of mystery. He suffered from mental illness and was institutionalized several times. His disruptive behavior, his offbeat logic, and his long periods of silence affected our family and shaped me profoundly. My father’s life was tragic and allowed me to question what we considered “normal” and what we considered “strange.” At times, sanity is like a clearly defined rainbow with distinct colors and borders, but once I drew nearer, those borders blurred. Because of my father’s struggles, I started to question what our society defined as rational behavior and what it means to strive for soundness of mind. Both of my parents were models of courage.

Website: www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/juan-delgado or www.juandelgadopoet.com

Instagram: jdwordpoet

Other: . https://www.nytimes.com/2016/02/22/arts/design/a-bruised-san-bernardino-shows-cultural-stirrings.html https://video.kvcr.org/show/expressions-of-art/ https://engagingthesensesfoundation.com/poet/juan-delgado/ https://www.poetryfoundation.org/articles/70107/vital-signs https://www.csusb.edu/beyond-fences

Image Credits

The photograph of me (side view) was done by Thomas McGovern.