Dora E. McQuaid | Award-winning Poet, Activist, Speaker and Teacher

We had the good fortune of connecting with Dora E. McQuaid and we’ve shared our conversation below.

What was your thought process behind starting your own business?

One Woman’s Voice grew of its own accord, in stages that seemed to morph one to the next, and to lead me along with it. While considering this question, I’ve become more aware of that sense of having been led or carried along into this way that I live in the world, and the work that I do, writing and speaking, teaching and consulting, listening and communicating in the various mediums available to me and the various roles that I serve with this One Woman’s Voice that is uniquely mine. One Woman’s Voice serves as a platform for all of these components of my creative and professional work, as poet/writer, activist, speaker, teacher and consultant. I started with writing poems as a little girl. As a young adult, I spent many years focused on my education, doing research on Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act as it related to Organizational Communication, Gender Studies and Leadership, while learning to teach, to perform and to articulate myself across my Undergraduate and Graduate programs at Penn State and during my earliest teaching experiences there. Academia taught me how to ask questions and how to research, and also how to listen across disciplines and audiences. Following graduate school, my life led me to a brief moment in banking in my effort to experience corporate culture and its structures. I catapulted from banking in Wilmington, Delaware, to relocating far from any home I’d ever known, hoping to strip away the years entrenched in academia and the mindset and value system of banking, both of which delivered me to a sense of deep dislocation from myself, from my own voice, and even from my own truth.

In Northern Kentucky and Cincinnati, Ohio, I discovered a community of discordant conservatism burgeoning with wild creativity and cultural transformation, and an artistic community that welcomed me, where I began to integrate the various aspects of myself and my experiences. I taught briefly at the University of Cincinnati as I began consulting on sexual harassment and diversity issues based on my graduate research at Penn State, as I began to listen deeply enough to hear my own voice and to begin writing again. The writers and musicians of Cincinnati’s vibrant Arts scene were so generous in their support and inclusion of me as I tested both my poems and myself in their midst, and I finally returned to myself in a way that had been lost to me during the previous years. In the process, I was learning to balance these longings and the various roles of poet, teacher, speaker and activist, and I began to build a life upon their opportunities as they arrived. And then my life was unexpectedly uprooted by violence.

After returning to Penn State, I was nearly murdered by a former boyfriend with whom I had had a brief and troubled relationship that I’d ended due to his mounting jealousy, suspicions, rage and abuse. I survived a night with him with a gun, and a many-months long ordeal of my leaving my new, and second, teaching post at Penn State, as well as my home and my life behind, running to stay alive – until I realized I had to go back to fight for myself and to live free. Prior to him, I’d had a history of experiencing violence in a baffling array of its forms, as so many women do. Having to fight for my life and my freedom forced me to finally come to terms with that history and begin to reclaim myself from it. Across those many months of terror and self-doubt, determination and grace, the writing saved me.

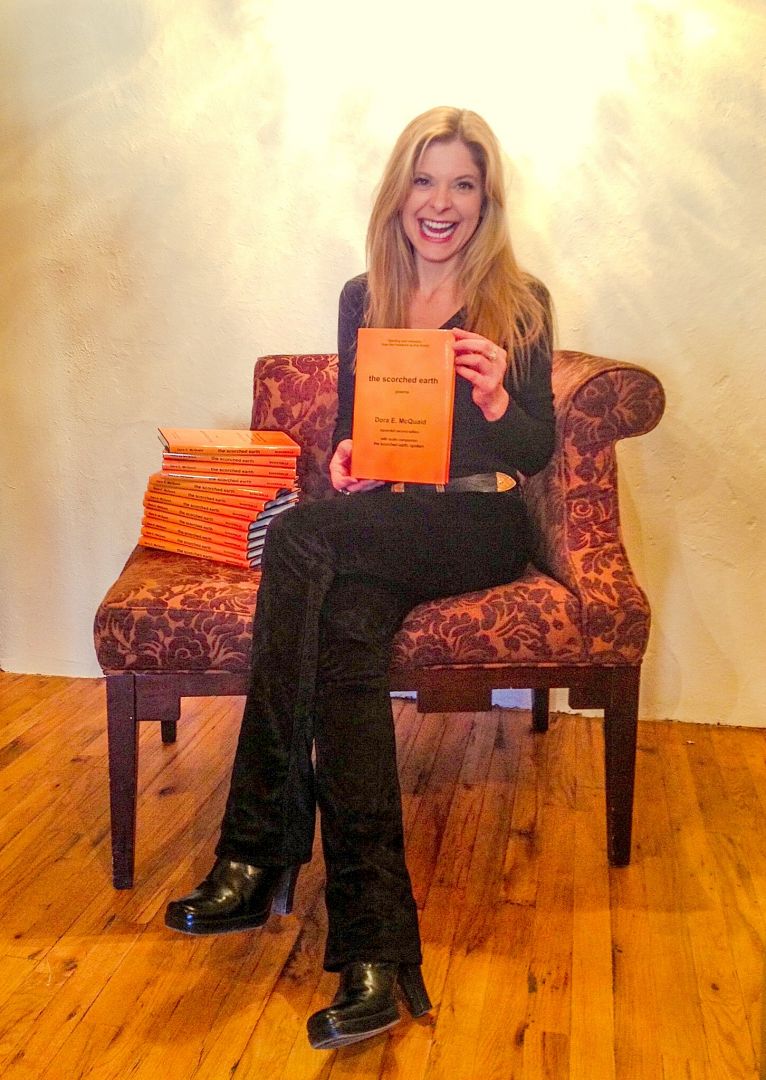

I wrote my way back to myself, to the deeper and truer self apart from the history of violence I’d known or the statistic I’d become and the deep undoing of the woman I thought I was. I wrote my way back to the truth within myself that cannot be altered or mitigated by circumstance or experience. During this period, I wrote my first book of poems, the scorched earth, when my heart felt like a fledgling beating with hope and possibility, as I was healing from that history. I returned to teaching at Penn State while fighting for myself, incorporating activism and social justice, healing and empowerment, and their intersections with the Arts, into each aspect of my life and role I was serving. I self-published the scorched earth, at a time when self-publishing was still considered vanity, with a colleague at Penn State actually telling me I was “committing career suicide” in making that book public. But I self-published it anyway because I felt called to do it, to tell the truths that book told when no one was telling those truths publicly, realizing that standard publishers would not risk that book precisely for the truths it told in 1999. Two years later, I recorded the first audio companion to the scorched earth, the scorched earth: spoken, at the request of Susan Kelly-Dreiss, Founder and Executive Director of the Pennsylvania Coalition Against Domestic Violence, who was using my poems in speeches and trainings across the state. The National Resource Center on Sexual Violence distributed both the scorched earth and the scorched earth: spoken as my writing, activism and voice stretched.

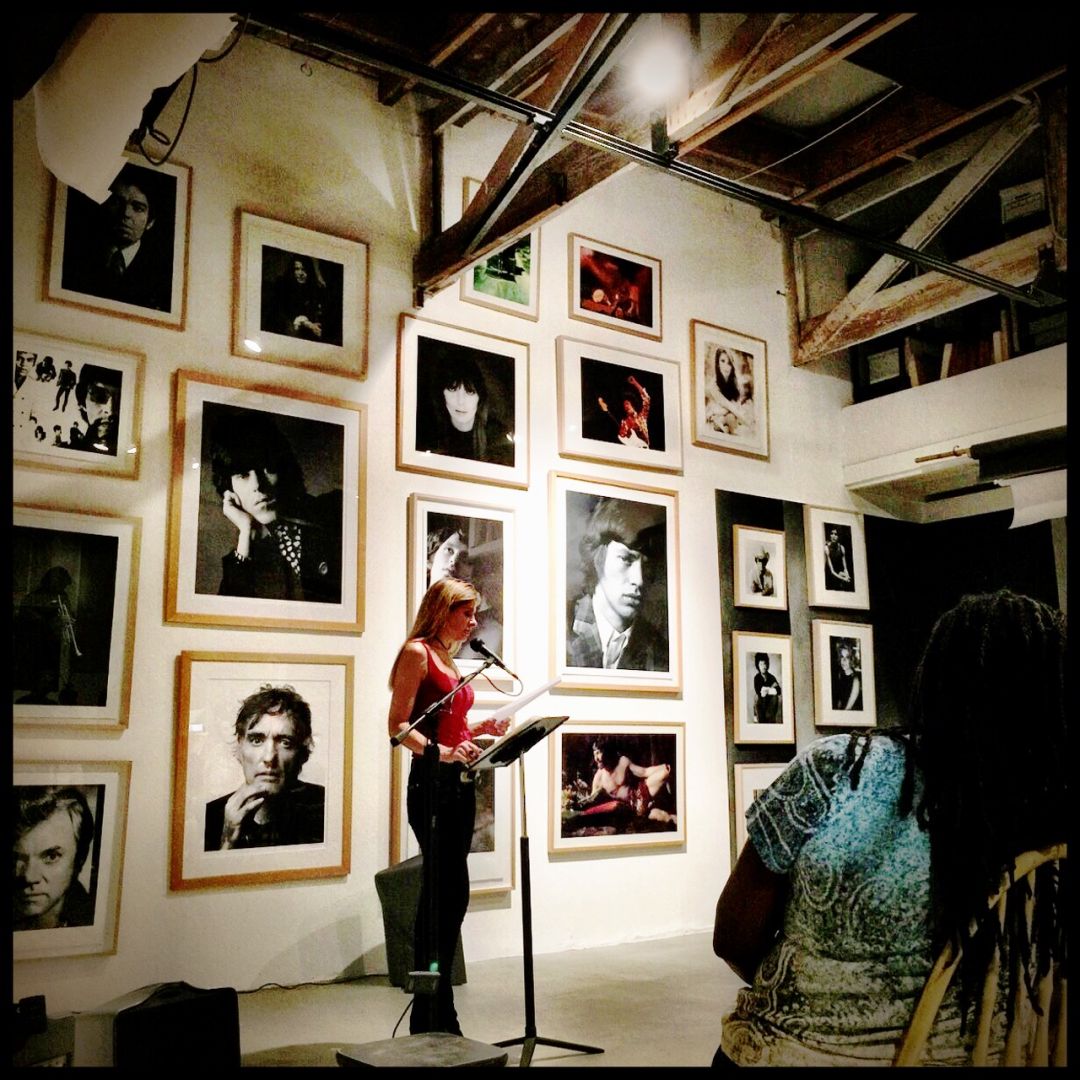

As a result, speaking and consulting on domestic and sexual violence, as well as healing and empowerment, became the primary focus of my work, with sexual harassment and diversity issues secondary. Teaching activism and social justice, and their intersections with the Arts, took precedence over public speaking and small group communication, and the events and organizations with whom I worked expanded from academia, government and the corporate world to shelters and churches, prisons and judicial systems, nonprofits and outreach services, festivals, conferences, television, and radio. A short documentary film was made about my story and my work, also entitled One Woman’s Voice, by Kate Bogle. I began to collaborate widely with an array of other artists, activists, and cultural creatives, across disciplines and agendas. I was commissioned to write the poem, Around This Table, to commemorate the 25th Anniversary of the Pennsylvania Coalition Against Domestic Violence, benefitting The Memorial Fund for Women lost in domestic violence homicides as a national poster campaign between 2001 and 2018. In 2018, I was inducted into the Wall of Honor by the Unionville – Chadds Ford School District in Chester County, Pennsylvania, where I attended middle and high school, in recognition of my lifetime achievements and contributions. I’ve also been honored with a Pushcart Prize nomination for poetry in 2014, as a 2012 Remarkable Woman of Taos, New Mexico, and with the 2011 New Mexico Woman Writer’s Fellowship Award from A Room of Her Own Foundation. In 2003, I was awarded the Pennsylvania Governor’s Pathfinder Award and recognized by the Pennsylvania Senate, and the Penn State production of Eve Ensler’s The Vagina Monologues honored my work with a Vagina Warrior Award in 2005. And then, 14 years after I first self-published the scorched earth, it was released by an award-winning publishing house as a second, expanded edition, with the the scorched earth: spoken Audio Companion, a 25-page Discussion/Study Guide and an extensive listing of International Resources for Survivors. The Foreword was written by myself and Eve Ensler, who wrote The Vagina Monologues and In The Body of The World. This second, expanded edition was released in the aftermath of my image replacing that of Jerry Sandusky’s, former Penn State football coach and convicted pedophile, in the Inspiration Mural near Penn State following his 45 convictions in 2012. The publicity and attention surrounding that moment of recognition was both gratifying and excruciating, as was the book tour that followed. As One Woman’s Voice stretched, I stretched with it, following its lead and echo until I left Penn State and academia to focus on poetry and activism, speaking and consulting, and exploring this one voice that I have been granted. Although I wanted to find ways to have the history I had survived serve other people and support other survivors when I wrote the scorched earth and began to advocate for coordinated systemic change around the global pandemic of domestic and sexual violence, I never anticipated how that trajectory has unfolded, or all of the blessings it has offered along the way.

No one has been more surprised than me by that unfolding or by the life I now live as a result of it. I went from being a woman who was nearly silenced by violence to being a woman who refuses to be silenced, supporting other people in raising their voices to claim themselves and the lives they long for and deserve. I say often that I did not choose this path, but that it chose me. I merely answered its call, and I am so grateful that I did. It’s an honor to be one voice among the many voices in the current uprising for justice and change, equality and community, hope and empowerment that we are experiencing across every sector of society around the world. It is an honor, as well, to support other people in speaking their truths as they claim the lives that want to live through them, as we all contribute to this unprecedented moment of both individual and collective change and transformation. We are each given one voice, and using that voice truly does have the power to change the world, at a moment when I believe the world needs us to bring ourselves fully to it, and to contribute to both its survival and evolution, as well as our own.

How do you think about your personal finances and how do you make lifestyle and spending decisions?

Yes, I do have a budget for both the professional and personal aspects of my life to best manage an appropriate balance between the two. That budget varies annually, based on the nature of my work during the previous year and an array of factors, including income, expenses, family needs and commitments, current and prospective clients, speaking and/or consulting commitments, degree of public exposure, and whether I am doing more public work (such as a book and/or speaking tour, teaching, or organizational consulting) or private work (such as working on my next book, working oneon-one with individual coaching clients, or researching and developing new projects).

I also assess at the beginning of each year the possible large expenses I may need to manage across that year, both professionally (website development, new technology, legal counsel, logistical expenses for upcoming residencies, fellowships and travel) and personally (new vehicle, new home/home expenses, family needs/commitments, travel, and any expected specific health needs, etc.) Spending decisions are made based on prioritizing the top three needs in both the professional and personal categories, and then mapping action steps and a schedule to manage each priority. Of course, best budgeting efforts are often confronted by life announcing unpredictable factors, and so I’ve learned to leave a cushion financially in the event that I need to reassess and reprioritize as the year ahead unfolds. For example, during the pandemic, I could not do any public work as planned, so I maximized the opportunity that created to work with website designers to entirely re-platform my website, which took a tremendous amount of time, focus and team planning that was perfect for the first 18 months of the pandemic. As we began to come out of the pandemic in 2022, I needed to buy a new vehicle after I was involved in a serious auto accident that totaled my car, another unexpected and critical expense that I had to manage. Each year presents different priorities, so I do my best to anticipate those priorities and plan accordingly, while leaving a buffer to catch me when the unexpected happens.

Risk taking: How do you think about risk, what role has taking risks played in your life/career?

Risk. It is everything. It is core to my work, to my life, to my way of living and being in the world. I’ve risked everything over and over again, including my own identity, security, and comfort. I’ve risked my career and professional credibility in speeches and stances, and in my activism and advocacy. I have risked my own life, and even the lives of people I love, by standing up to systemic oppression and injustice as a poet, activist, speaker and teacher. I have left established positions and careers, homes and communities, former selves and outworn agendas, to stand on the edges of what might be calling me forward, to listen and learn anew, to explore and push boundaries and convention. As I said in my response to a previous question, decades ago I wrote a book, the scorched earth, and self-published it, disregarding advice from colleagues who warned me it was career suicide, only to have that book reissued by an award-winning publisher 14 years later as a second, much-expanded, multi-media edition with the Foreword written by myself and Eve Ensler, who wrote The Vagina Monologues and In The Body of The World. This second edition was released in the aftermath of my image replacing that of Jerry Sandusky’s, former Penn State football coach and convicted pedophile, in the Inspiration Mural near Penn State, following his 45 felony convictions in 2012. I’ve risked stability for freedom, acceptance for authenticity, ostracism for solitude, reputation for originality. I’ve repeatedly navigated stalkers and death threats, criticism and retaliation, and even silencing in my efforts to just be myself, to live my life the way I feel called to live it, and to stay true to myself. I believe that most of living, loving, working, being all comes down to risk, and to risking ourselves. It is all risk, and the flipside of that to me is faith.

Years ago, in rush hour traffic on I-95 South, I got cut off at 75 miles per hour by a commercial delivery truck whose back door was emblazoned with: IF THE TASK IS TOO BIG, YOUR GOD IS TOO SMALL. Over the years, that moment and its message morphed within me into: If the risk is too big, my faith in what is possible is too small. Because the risks I’ve taken have always borne their blessings, even when they have caused me to stumble or seemingly fail. I survived. I still learned, I still grew. I evolved into the next becoming of my self. And I’m still here, still showing up, still wildly intrigued by all that is possible within us and between us. But I don’t know what is possible until I move out to meet it, until I am ready to risk now for what is next possible. And I want to live there, inside of what is possible. Risk, I believe, is worth all of what is possible.

Where are you from and how did your background and upbringing impact who you are today?

I had the great benefit of growing up bicoastal, between Philadelphia and Southeastern Pennsylvania and the San Francisco Bay Area of California during the 1970s and 1980s. Although I was born in Philadelphia and spent the majority of my childhood and teenage years in Chester County, Pennsylvania, my family moved to the Bay Area during its cultural revolution in the mid 1970s as my father’s career with the Clorox Company progressed. Both my mother and father were from Philadelphia’s Main Line, from large Catholic families with strong work ethics and deep connections to their respective communities. Both of my parents were divorced when they met in 1971, when divorce was still uncommon, especially in the Irish and Italian Catholic families from which my parents came.

My mother had survived a horrifically abusive first marriage to my biological father, which ended before I was 2 years old, sparing me from ever really knowing him. Her independence and fierce determination to reclaim her life on her own terms as she raised me and my brothers in the aftermath have served as both Inspiration and example to me, especially when I had to fight to reclaim my own life after experiencing domestic violence myself. My mother met the man who raised me, who I refer to as my father (my only father, actually), when I was 3 years old, and 6 weeks later, I was the flower girl in their wedding. The love, commitment and partnership between them provided the stability needed to make a family of us all. As much as my mother’s wounding influenced me, her fierce courage, strength and ability to fall in love again inspire me to this day. My father’s kindness and integrity, as well as his deep faith and commitment to living in service to other people guided me from an early age and continue to influence my life and decisions daily. We moved to the Bay Area in 1976 as San Francisco’s culture was exploding. Between the Civil Rights, Women’s Rights and LGBT Rights movements, the rapid influx of radicals and hippies, the expanding counter culture and sexual revolutions, passionate protests and community activism, San Francisco was a city where minorities and the marginalized were welcome and active, as the music and arts scene reflected the wild, vibrant energy of the city and its diversity. Even as a kid in elementary school, I was aware of the city’s energy and upheaval, enthralled by the many differences between San Francisco’s and Philadelphia’s cultures and values. When we returned to Chester County, Pennsylvania, as I was beginning middle school, I was crushed, and determined to return to Berkeley for college as my father’s position with Clorox prompted my parents to keep a home close to the UC Berkeley campus for many years. As a “California kid”, I did not fit in with my Chester County, Pennsylvania classmates. Most of them had never seen a skateboard before, let alone a teenage girl riding one. My exposure to the diverse populations and radicalized politics of San Francisco left me ill-prepared for the conservative and often discriminatory perspectives I witnessed in some of my peers.

I was labeled as a lesbian at one point by a bully classmate, who believed that calling me a lesbian was an epithet. After the years spent in San Francisco, I didn’t even understand at first that she was trying to condemn me with that label. I have no doubt that my experiences in and exposure to San Francisco’s social and political revolutions of the late 1970s deeply influenced my own activism and sense of agency as I grew and became more socially and politically engaged. Chester County, Pennsylvania, provided me with an excellent education, an opportunity to develop my independence, to explore my tom-boy tendencies in sports, and to appreciate the history of the United States with its birth in revolution and independence, as the Revolutionary War was fought in the countryside surrounding my family’s home and the fields I ran for Cross Country and Track through high school. Chester County was built by revolutionaries and rebels, as well as activists and artists, whose celebrated legacies became part of my education, and my sense of possibility and empowerment, just as San Francisco’s volatile revolutions and visionary inclusivity did. The combination of influences from that bicoastal upbringing are indelibly woven into me. While the East Coast offered me structure and history, the West Coast expanded my creativity and sense of radical possibility, as my parents modeled the necessities of being brave in the face of challenge, kind in the face of hardship, active in the presence of injustice, and willing to be of service to uplift and support other people, especially those in need.

What is the most important factor behind your success / the success of your brand?

I believe in staying true to myself, and within that truth, being as authentically myself as I can be. These principles encompass many aspects, including my integrity, values, commitments, originality and truth, as well as my voice and my spirit, among others. Each of those factors, individually and combined, require that I trust myself, even when I am faced with doubt, criticism, threat, ostracism, or injustice, OR conversely, when I am faced with validation, acknowledgment, inclusion, celebration, and reward.

Learning to trust and honor myself, my originality, and my voice took me decades. And continuing to trust all three requires constant awareness, reflection and recalibration. If I am to tell the truth of my experience, perspective, and spirit – and telling the truth, my truth, is another essential factor that contributes to my success – I have to stay true to myself. I have to cultivate that trust in myself daily and be willing to take the risks required to remain as authentic as I can be. So much of my personal life has been lived in the public, has been purposefully and actively brought into the public realm as a means of activism and change, of creating community, of fostering justice and engagement, of exploring healing and empowerment, on both the personal and collective levels. By risking myself publicly as a poet, activist, speaker and teacher, I want to show other people that we are not alone in our experiences and their truths, that we are more powerful than we often believe ourselves to be, and that we are stronger when our shared experiences unify us and galvanize us to stand together.

What value or principle matters most to you? Why?

The principle that I base my entire life upon, both personally and professionally, is to be of service. I have always wanted to have my life, my presence, my voice and my work to be of service to others in ways that encourage people to live fully into themselves and the potential of their own lives, to trust themselves and their creativity, and to develop as fully as possible into the person they are meant to become. I believe that when we commit to becoming the fullness of who we are meant to be, that fullness has the potential to change our lives and to contribute positively to the lives of the people around us. Living from, and into, our individual truth often allows us to realize that we are far more powerful than we have been led to believe, and when we are empowered, we often empower others.

Work life balance: how has your balance changed over time? How do you think about the balance?

What a question: Work/life balance?!? Does that even exist as a possibility? The challenge to strike that balance is one of the most consistent, defining experiences of my life. I have always been truly baffled by the concept of limits. Even as a little girl, I did not understand pacing myself, or the need for it, let alone having actual limits to what I can do or be. The human body, which I call the “little human suit,” is an astonishing vehicle with which to have been blessed to navigate this existence. I am almost daily in awe of the intricate and elegant design of that simultaneously fierce and fragile little human suit that is capable of both the miraculous and banal, the visionary and the mundane. And yet, I struggle with comprehending – and accepting – that the human suit comes with inherent limits that restrict what I can explore or create, accomplish or build, maintain and BE on any given day. This confusion about, and refusal to accept, the limits of my body and my being has led to a lifelong history of relentlessly pushing well past those limits to the point of exhaustion, illness, injury and, on rare occasion, even collapse.

In some of those instances, the recovery times have been excruciatingly long and convoluted, only further testing my patience with my little human suit and all that it requires of me to run well. From my earliest memory, I have been aware of always trying to do too much, to be too much, and to demand too much of what my physicality is capable of performing. I have been challenged by this “balance” across my lifetime, and still find the practice to be one that requires endless pendulum swings, with balance being struck periodically and briefly. Complicating the challenge has been the lack of a distinct separation between my public work and my private life, especially in regard to my public activism around domestic and sexual violence, sexual harassment, and healing and empowerment initially being fueled by my personal experiences, which formed the basis of my writing, speaking, teaching and consulting for decades. The melding of my private and public lives can make rest and retreat more challenging, and the privacy they require is often elusive at best. However miraculous the body is, I’ve had to learn again and again to respect its vulnerabilities and frailties, as well as its need of constant tending and forgiveness. As a result of genetics combined with my pace of living and my confusion around my limits, I developed multiple autoimmune issues in my mid-thirties that demanded I learn to better tend to myself, prompting me to at least attempt to maintain a daily routine that better supports my health and well-being. After TWO life-altering auto accidents exactly 17 years to the day apart from each other in 2004 and 2021, I am again learning the necessity of prioritizing my self-care and the tending of my body and my spirit. The most recent accident in 2021 forced me to create more space in my daily life for myself, which became shockingly easy to do when my injuries left me unable to work for an extended period of time. Suddenly, I had a level of unprecedented freedom to simply take care of myself, and to prioritize my healing and recovery. As a result, I am learning, finally, how to strike and maintain a more sustainable work/life balance on a consistent basis, which has been a remarkable and unexpected experience.

After nearly three years of having to focus on my healing and reclaiming my fullest health again, I am now finally resuming work again, slowly returning to projects necessarily delayed in the aftermath of the 2021 accident, such as my next two books, the final development of my fully re-platformed website which was unfinished when it went live days before that 2021 accident, and one-on-one coaching. If you ask me this question one year from now, I hope to have incorporated what I have learned about maintaining that balance as I continue to heal and expand the scope of my capabilities and possibilities once again. I’m intensely excited and curious about where both my life and my work will next lead me, while simultaneously deeply grateful to have had the opportunity to focus on healing and reclaiming both my health and my life, along with their many possibilities for my future.

What’s the end goal? Where do you want to be professionally by the end of your career?

My end goal is also my current goal, multi-layered and varied. I want to be present, to be open and available to inspiration, change, and guidance. I want to be creative, to be curious, to continue to explore and engage the world around me and the people, creatures and elements in it. I want to be of service to other people. At the end of my career and on a daily basis, I want to know that I showed up as fully as possible with all of myself available to living and being, that I did my best to stay true to myself, and that I positively contributed to the betterment of people’s lives and their sense of possibility for themselves. When I finally slip out of this lifetime and my little human suit, as I have long called my body, I hope to do so knowing that I made a positive difference in the lives of others, and within the systems that hold us all.

Why did you pursue an artistic or creative career?

I did not actively pursue a creative career or path. I believe I was born into it, or perhaps borne of it. No matter how many times across my life I have sidestepped or tried to deny that creative calling, it has always come back around as if actively choosing me, rather than me choosing it. I knew from the youngest age that I was a writer, as if it was simply an innate and defining part of me from the beginning.

I remember being confused by adults asking me what I wanted to be when I grew up, as if I needed to WAIT until I actually grew up to be what I already knew I was. I recall answering that question, even before the age of 10, with the simple proclamation: I AM a writer. I am a descendant of Irish storytellers and strong women, all of whom had amazing lives and family stories that were often shared around the kitchen table, prompting my fascination with both the written and spoken word, with language and its power to unify and uplift people gathered together. I learned hope and courage from those stories, and rhythm and cadence from the telling of them. By the time I was in high school, I was known for writing, enough to have one of my English teachers begin calling me Emily, after Emily Dickinson, with other teachers and students following suit. My propensity to write at any time, anywhere, even sitting down in the high school hallways to write when an idea came to me, was surprisingly supported by my teachers, who continue to encourage and celebrate me to this day. As a teen, I could not have known the winding, stutter-step, stop/start path I would take to live into the poet I have become, or that poetry would also allow me to combine my other areas of education and expertise, passions, and commitments through activism and speaking, teaching and consulting, healing and empowerment. I could not have known that writing would years later save my life at a moment when I did not believe I could even save myself.

The history of violence I had known and the self-doubt and confusion that history created despite my academic and career successes left me feeling disempowered and silenced, especially after nearly being murdered by a man with whom I’d had a brief relationship that I ended due to his quick escalation to abuse. While writing one morning at the National Poetry Slam National Finals in Chicago, I realized I had to fight for myself in order to finally live free of both the violence and the impact of its history. The writing I did during that long ordeal and the healing that followed saved me. I wrote the truth of my own life and experience and, in the process, I wrote my way back to the truth of myself. During this period, I wrote my first book of poems, the scorched earth, which I self-published at a time when selfpublishing was still considered vanity. I felt compelled to tell the truths that book told when no one was telling those truths publicly, realizing that standard publishers would not risk that book precisely for the truths it told in 1999. Two years later, I recorded the first audio companion to the scorched earth, the scorched earth: spoken, at the request of visionary leader Susan Kelly-Dreiss, Founder and Executive Director of the Pennsylvania Coalition Against Domestic Violence, who was using my poems in speeches and trainings across the state of Pennsylvania. The National Resource Center on Sexual Violence began distributing both the scorched earth and the scorched earth: spoken as my writing, activism and voice stretched. Simultaneously, my teaching, speaking and consulting expanded to incorporate activism and social justice, and their intersections with the Arts, as the events and organizations with whom I worked also expanded internationally. I began collaborating with an array of other artists, activists, and cultural creatives, across disciplines and agendas, as my work reached wider audiences and garnered an array of awards and recognition. 14 years after I first self-published the scorched earth, it was released by an award-winning publishing house as a second, much expanded edition, with the scorched earth: spoken Audio Companion, a 25-page Discussion/Study Guide and an extensive listing of International Resources for Survivors. The Foreword was written by myself and Eve Ensler, who wrote The Vagina Monologues and In The Body of The World. This second edition was released in the aftermath of my image replacing that of Jerry Sandusky’s, former Penn State football coach and convicted pedophile, in the Inspiration Mural near Penn State following his 45 convictions in 2012. The publicity and attention surrounding that moment of recognition was both gratifying and excruciating, as was the book tour that followed. Although my life repeatedly drew me away, the writing always came back for me, leading me back to my own truth and voice, and their intersections with speaking and teaching, activism and social justice, healing and empowerment. I left academia to focus on poetry and activism in 2006, when I finally accepted what the much younger me had known: I am a writer. And the writing chose me again and again, and gave me an expanding range of mediums and roles with which to explore my voice. I was meant to write and speak and teach, to create and collaborate, and to add my voice to the many voices in the current uprising for justice and change, equality and community, hope and empowerment that we are experiencing across every sector of society around the world. No one has been more surprised than me by the unfolding of my life and career, or by the life I now live as a result of it. I went from being a woman who was nearly silenced by violence to being a woman who refuses to be silenced, supporting other people in raising their voices to claim themselves and the lives they long for and deserve. As I mentioned before, I say often that I did not choose this path, but that it chose me. I merely answered its call, and I am so grateful that I did.

It is a privilege and an honor to live as I do, and to support other people in speaking their truths as they claim the lives that want to live through them, as we all contribute to this unprecedented moment of both individual and collective change and transformation.

Tell us about a book you’ve read and why you like it / what impact it had on you.

This question is torturous to answer. As a lifelong avid reader and poet/writer, with a long history in academia and activism, there are so many books that have influenced, galvanized, moved and deeply affected me. From the poetry of Rumi, the 13th century Persian poet translated by Coleman Barks, to the memoirs of Karen Tania Blixen who wrote as Isak Dinesen, to the writings of public intellectuals such as Howard Zinn, Noam Chomsky and Audre Lorde, and to the poetry, fiction, non-fiction, essays, and biographies of a wide array of writers, choosing one book is nearly impossible. While considering this question, however, I’ve returned again and again to the classic memoir by Beryl Markham, West with the Night, which I have read countless times. Beryl Markham was born in England in 1902, but was raised by her father from age 4 in Kenya, then still colonial British East Africa. Beryl’s life was extraordinary, beginning with her unconventional and rather wild upbringing in Kenya, which drew her from a young age into her father’s horse racing farm as both a rider and trainer, and ultimately launched her life as an unprecedented adventurer and aviatrix. At the age of 33, Markham became the first person to fly the Atlantic solo, East to West, from England to Canada, which she did in a 20-hour, nonstop flight.

West with the Night is Markham’s memoir of her remarkable experiences as a horsewoman, adventurer, and aviation pioneer during the 1900s, as well as her upbringing and its influence on the unfolding of her life until the age of 40, when the memoir was first published in 1942. The memoir was well received, ranked #8 in National Geographic’s 100 Best Adventure Books List, and even garnered rare and generous praise from Ernest Hemingway. She was a force of nature, and nature itself formed her and claimed her for its own. The scope and arc of her life show her continued fascination with and determination to explore as much of the untamed natural world as she could, living outside of convention and pushing every boundary possible into her next adventure. Beyond her life, her writing of it is stunning, breathtaking, articulate and deeply moving. My first reading of West with the Night left me utterly undone. I was truly breathless with her writing, her exquisite command of the language, and her almost preternatural presence to both the beauty and brutality of a still wild Africa. Markham lived well beyond convention, with a fearlessness and adamance that still leaves me in awe. She refused to be limited or restricted in any way, and lived the length of her rare life by her own lights, as did her contemporary and friend in Kenya, Karen Tania Blixen, who wrote another gorgeous memoir of Kenya during the same time, Out of Africa, under the pen name of Isak Dinesen. Markham was a fiercely independent woman, who refused constraint and lived of her own accord on the land that spoke to her and in the sky that held her.

Her ability to write of her own life as exceptionally well as she did delivered a classic, timeless memoir of a woman who still intrigues and inspires me, decades after my first reading of West with the Night. I will leave you with two quotes of Beryl Markham’s from West with the Night that I have written as both beacon and reminder in many of my journals over the years: “A map says to you: Read me carefully, follow me closely, doubt me not… I am the earth in the palm of your hand.” AND: “There are all kinds of silences and each of them means a different thing. There is the silence that comes with morning in a forest, and this is different from the silence of a sleeping city. There is silence after a rainstorm, and before a rainstorm, and these are not the same. There is the silence of emptiness, the silence of fear, the silence of doubt. There is a certain silence that can emanate from a lifeless object as from a chair lately used, or from a piano with old dust upon its keys, or from anything that has answered to the need of a man, for pleasure or for work. This kind of silence can speak. Its voice may be melancholy, but it is not always so; for the chair may have been left by a laughing child or the last notes of the piano may have been raucous and gay. Whatever the mood or the circumstance, the essence of its quality may linger in the silence that follows. It is a soundless echo.” ― Beryl Markham, West with the Night, 19402

Nominate Someone: ShoutoutLA is built on recommendations and shoutouts from the community; it’s how we uncover hidden gems, so if you or someone you know deserves recognition please let us know here.