Meet Bonnie Griffin: Visual Storyteller & Researcher

We had the good fortune of connecting with Bonnie Griffin and we’ve shared our conversation below.

Hi Bonnie, why did you pursue a creative career?

“Puppet-maker’. I remember seeing this answer pop up at the end of a computer questionnaire that constituted my college’s ‘careers advice’. As an 18 year old with an equal interest in art and science, I found this suggestion completely hilarious at the time. I lived in a council house in a tiny village who’s only link to the outside world was a bus that ran every third Tuesday of the month, there didn’t seem to be much demand for puppet-making. Not knowing any jobs that combined art and science, and hoping to have some career stability I opted for a degree in Zoology, creative stuff would be something for my personal time. At the end of uni it struck me that I had been to all of my friends final year shows in art and architecture, but my thesis wasn’t exactly an appealing read to a non-scientist. I started to think about how to make scientific concepts as beautiful, surprising, engaging and inspiring as a great work of art. 15 years later, after various communication roles in ecology, museums, zoos and heritage, I finally made it to my dream job, working as a Natural History Curator. On paper it was the perfect creative biological career: high level science, wildlife conservation, storytelling through objects and room to flex my creative muscles with exhibition design. I was ready to dedicate my life to it but it wasn’t to be. My hard-won credentials were constantly questioned and undermined, the institutions were full of out-dated sickly systems and there was clique-y competitiveness in the natural sciences that I found exclusive and off-putting. I didn’t want to keep replicating the same old exhibition styles with the same old stories. I’d seen Isabella Rossillini’s Green Porno series, which to me set the bar for science communication but I’d lost confidence in myself that I could match, create or convince the decision-makers to realize something so ‘radical’. I sought refuge with the historians, conservators, ethnographers and artists, who seemed far more relaxed around new ideas, pushing boundaries, collaboration and skill sharing. This feeling was cemented when I met UK artist Jeremy Deller. I didn’t think a modern artist would have any interest in the old bones and taxidermy but he asked to see the collection. We talked about the stories that are wrapped up in the specimens, and how they could link out to folklore, land use, UK law, and ideas of cultural identity. He totally understood the collection which was incredibly validating. His exhibitions were articulate, bold, and so rebellious I couldn’t believe it. It all looked glorious; he told the story he wanted with the objects he wanted and I wanted to do things like that. Around the same time I met director Chris Hopewell, it was halloween and I was dressed as Famine with my home-made horse skull mask. I took off the mask to hear him better over the noise of the party and when he looked at the mask’s construction he and his producer Rosie Brind asked if I’d join them on their stop-frame animation for Radiohead. It was the first time I had felt welcomed into a project, and my skill set seemed to be recognized and appreciated, I jumped at the chance. A few weeks later I was working with the loveliest crew of people, in an environment of collaboration over competitiveness with everyone genuinely happy to share their expertise and ideas – they were my instant heroes. There I was having the time of my life making tiny props, clothes and yes, would you believe it, puppets! The computer had been right all along… Needless to say, I’m still not banking on a career in puppet-making, and I still have a love for natural history but now I’m focused on visual storytelling as my way to creatively communicate untold or suppressed stories, using in-depth research methods and creating accessible and engaging object-led exhibitions outside of traditional museums spaces. I found working in collaborative environments that foster creative co-sharing, honesty, quiet-egos and thoughtful, good quality outputs is where I thrive. This way of working isn’t exclusive to, or guaranteed in creative projects by any stretch, but creative spaces and people were the ones that made room for me.

Can you open up a bit about your work and career? We’re big fans and we’d love for our community to learn more about your work.

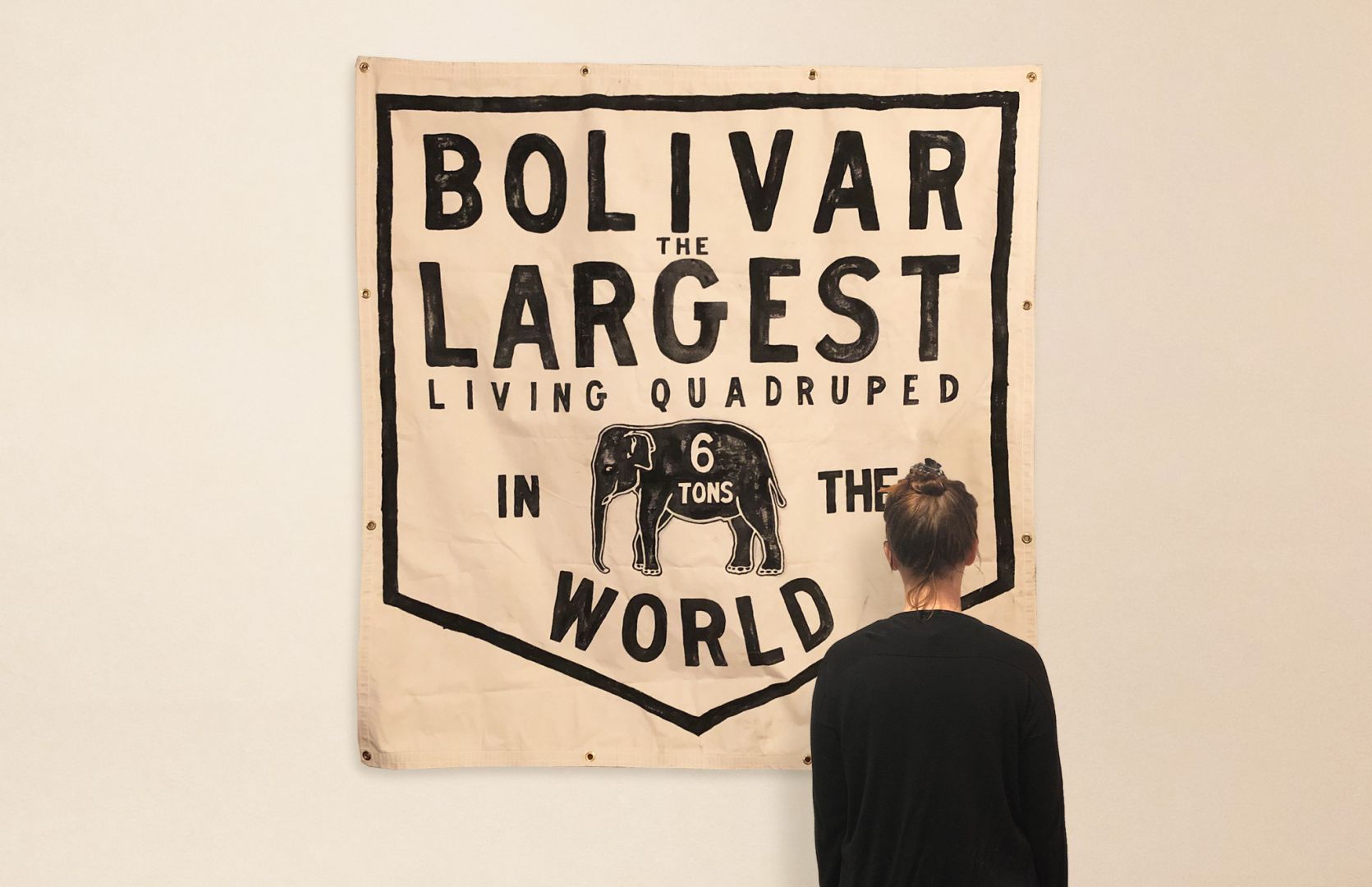

When I decided to leave my museums career, I was scared to lose my title as ‘curator’ (which had somewhat protected me from the skepticism over my expertise) but also gutted to lose the physical access to the collections. In leaving the institution I was released from the bureaucracy and creative restrictions, but I had struggled to fulfill my exhibition ideas as part of the institution, surely it would be impossible now I was going rogue. I felt my new challenge as an independent visual storyteller was how to tell a story with no objects, however the truth was I had had this challenge for many years. Collections are often products of someone’s special interest, or from the colonial past, collected and donated by the wealthy. This can create a collections bias, usually towards a white, male, European perspective. For a long time I had been wondering how to include new narratives, when these stories had been ignored or suppressed and when no artifacts were collected… I still had this question when I moved to California and stumbled across a 19th Century circus elephant called Bolivar. Although famous as the largest elephant in the world, Bolivar had been completely overshadowed by his rival Jumbo, who despite being a ton lighter, is still well known today. Bolivar is described on the Philadelphia Academy of Science’s website as ‘Philadelphia’s Unfriendliest Celebrity’ a legacy I felt was a little unfair for an animal subjected to the rudimentary animal husbandry knowledge of the time. I set out to find the truth about Bolivar and after two years of research, found there was so much more to his story. By the end I had become incredibly fond of Bolivar and I was itching to do an exhibition, but all that remained of his life were a few images and his dismantled skeleton which was off-show in Philadelphia. Of course it was impossible to find the money, time and space to somehow loan, transport, clean, re-articulate and safely display his skeleton. I still had no objects to work with. It wasn’t until I thought back to my last major exhibition that my ‘light-bulb’ moment came. I had worked with the Paleontology Dept to recreate a huge Jurassic Pliosaur, who’s fossilized remains were held in the collections. During this exhibition I had thought a lot about authenticity and how vital provenance is to museums work. A genuine artifact is invaluable and irreplaceable and is the basis for important research. Famously London’s ‘Dippy’ the Diplodocus caused a minor scandal when it became common knowledge that the assumed ‘real’ skeleton was a plaster cast replica. The reality is that fossils are often incomplete or squashed during formation and these distorted remains can be difficult to interpret for visitors. It’s normal to commission casts, models or drawings, based on the latest science to help ‘realize’ these creatures. However, it does require certain amount of imagination on behalf of the artist to ‘fill-in’ the missing or unknown parts. I began to realize that a lot of the objects I cared for were chimeras, combining the ‘real’ animal body with wires, glass eyes, clay and paint, in order to create a visually engaging object. Moreover, replicas had certain advantages; despite being less useful for research, they could be easily handled and didn’t require the climate controlled, protective museum environment. In some cases they were even more engaging than the original object. So, as obvious as it seems, I finally had my answer! I could create new objects and as long as I was upfront about the provenance, it was still possible to tell a story without an original artifact. I ended up telling Bolivar’s story by creating 5 elephant advertising banners, in the style of those worn by the circus elephants when they paraded through the towns. Instead of publicizing the circus, these banners now advertised Bolivar’s incredible qualities and linked to parts of his story explained in depth around the gallery. Despite working by myself, it was one of the most satisfying experiences of my life. I was able to deliver my narrative from start to finish, without compromise. Now I’m replicating this project for Bolivar’s keeper, Eph Thompson, who became the most famous elephant trainer in the world – an incredible achievement for a black man in the 19th century. I have pieced together this life story from over 100 newspaper articles documenting his extraordinary life which will be published as part of an exhibition on the Uncle Junior Project website in 2021. This time I am hoping to create a physical exhibition by asking artists, musicians, costume makers and circus performers to respond to Eph’s story and create artworks that will help bring tangibility to Eph’s life. Through meticulous research and the creation of engaging objects I hope to champion these forgotten stories and create legacies for these overlooked lives.

Any places to eat or things to do that you can share with our readers? If they have a friend visiting town, what are some spots they could take them to?

For entertainment: Hollywood Bowl La Bear Tar Pits Malibu Beaches Heritage Square Griffith Park Comedy Club To eat: SIlverlake Ramen Elf Freedman’s Deli Cosa Buena To hang: The Holloway Echo Park Lake Semi-Tropic

The Shoutout series is all about recognizing that our success and where we are in life is at least somewhat thanks to the efforts, support, mentorship, love and encouragement of others. So is there someone that you want to dedicate your shoutout to?

The Shoutout series is all about recognizing that our success and where we are in life is at least somewhat thanks to the efforts, support, mentorship, love and encouragement of others. So is there someone that you want to dedicate your shoutout to?

All my wonderful friends and family in Bristol (UK) and Katheryn Renton and Veronica Blair in California

Instagram: @bonnieandthebeasts

Twitter: @bonniebeasties