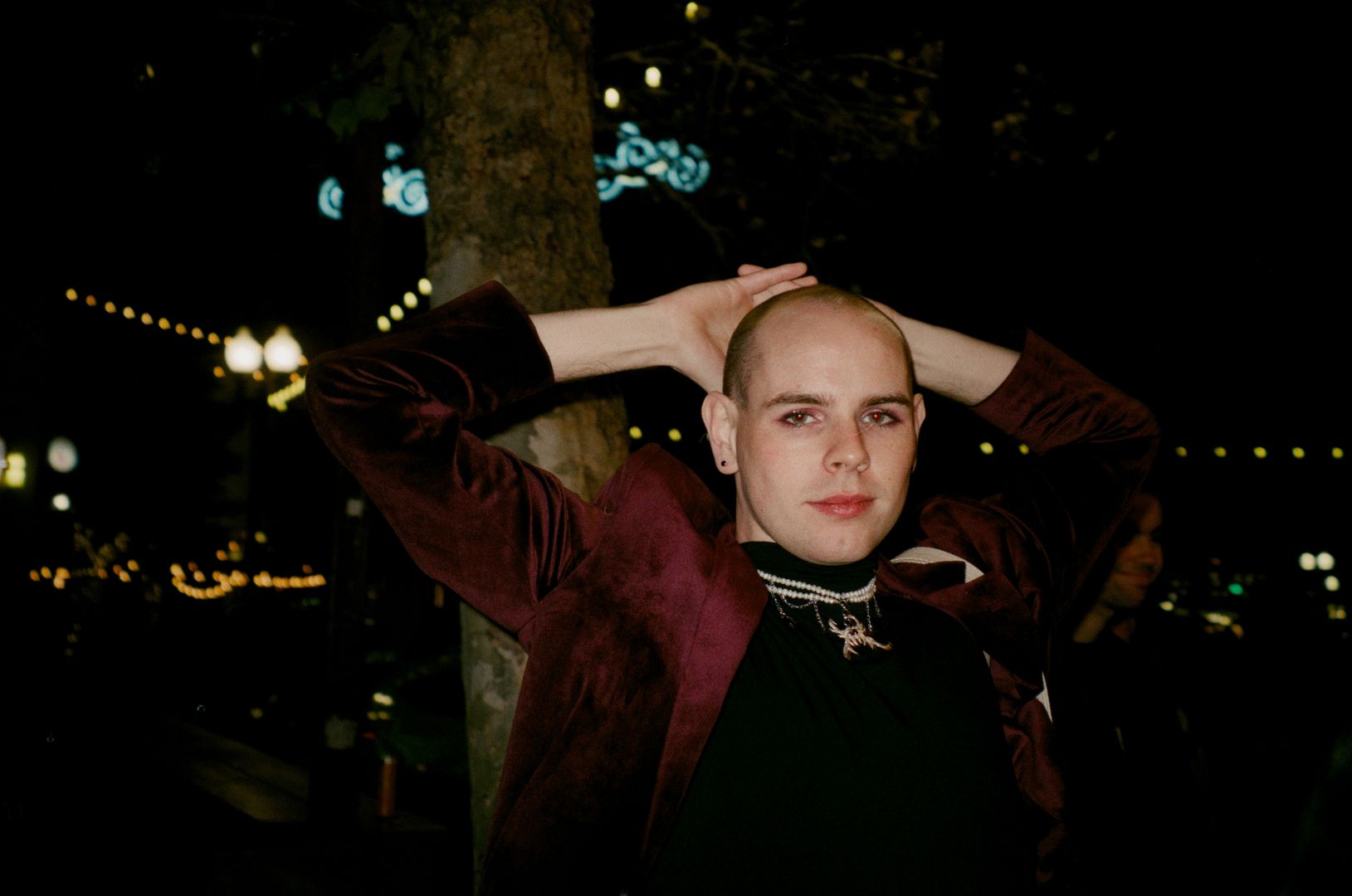

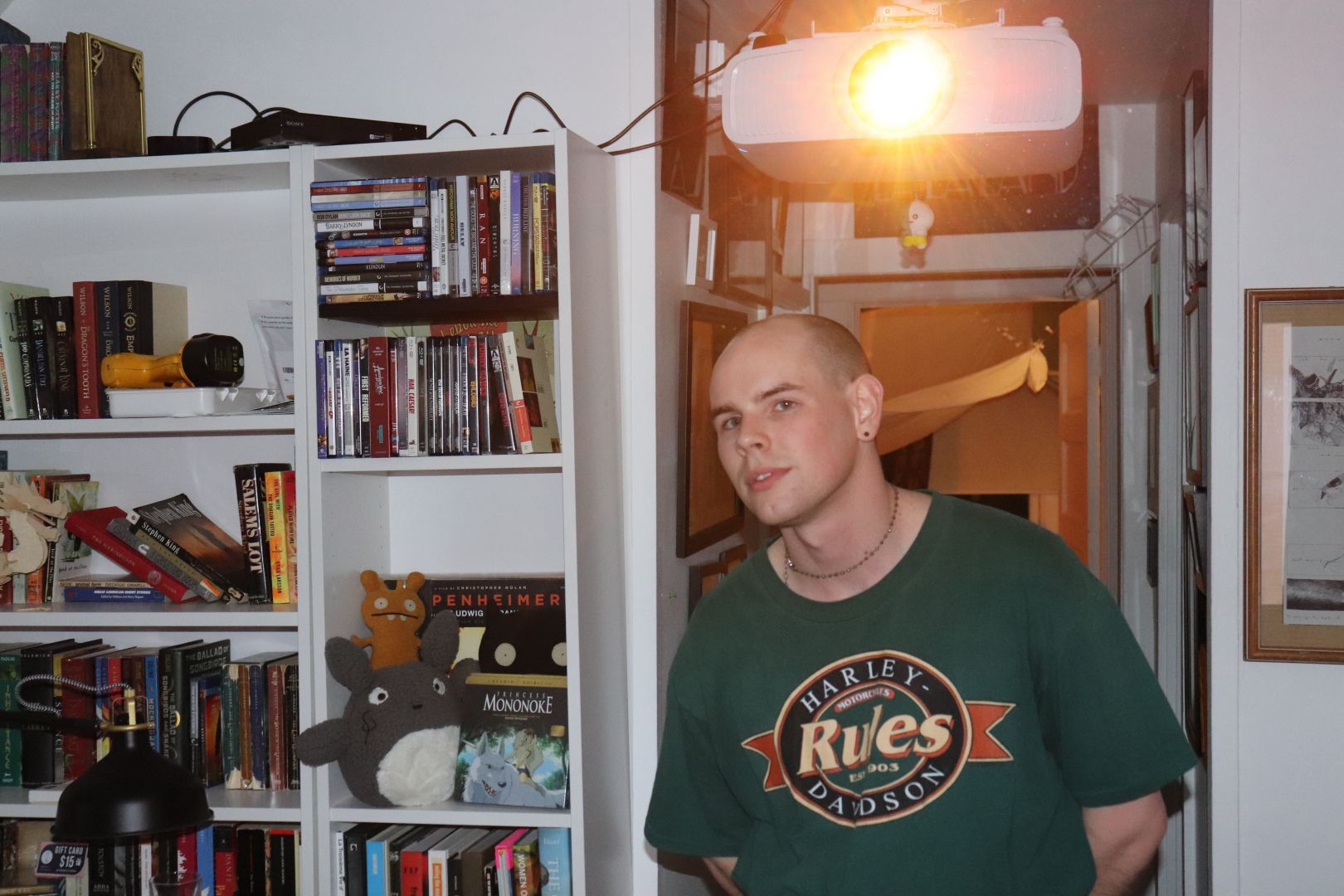

Meet Jess Taylor | Independant Filmmaker – Director and Producer

We had the good fortune of connecting with Jess Taylor and we’ve shared our conversation below.

Hi Jess, how do you think about risk?

It’s exciting: it’s an invitation to create, discover, sometimes even rebel. I don’t have much interest in making easily digestible work, and it’s very risky to ask your audience to exercise patience right now. Especially at the beginning of a career, without any clout or street cred. I’m a flick of a thumb away from being scrolled past, forgotten. But without taking that risk, I wouldn’t be able to craft the type of cinematic experience I’m committed to, both on-screen and on-set. There’s something so rewarding, as either artist or audience, about engaging with work that demands you practice an unexpected virtue – Ebert’s often quoted(and rightly so) as calling film an “empathy machine,” but it’s also a trial of patience and faith. The best films invite you to meet them halfway, and to sit for a moment (or several) before the catharsis and closure is revealed — if at all! And it’s very risky to ask that of a theater-going audience, almost impossible if they’re able to scroll right past. But I believe in the beauty and power of that type of cinema, I get a great sense of contentment in crafting that and I know the audience exists. I can’t be the only freak who likes this, ya know? The risk just means you have to be smart when you’re making the movie, so they’ll still let you make the next one. The other thing about risk is that it’s so thrilling — I’ve always been an adrenaline junkie and filmmaking has become a new conduit for the same sensations. I always want the set to feel alive, and artists light up when you give them a challenge with the right tools and timeframe to make it work. At the end of production, I want everyone to be proud of their work. So, ever since I had enough pull to produce real sets, I try to do something that feels risky. Sometimes that’s a technical risk, like “how are we going to time this dolly move so we catch the first moments of sunrise at the end of it?” Sometimes it’s an artistic risk, and that’s less of a brain-drain but more of a spiritual, soul-attuned challenge for me. The guiding principle for my last short film was to take some steps towards slow cinema and transcendental style, hit the same harmonies as the greats like Ozu, Weerasethakul, Malick, Dreyer. And that was as students! Five film students with borrowed gear and an AirBnB. And there are moments when we absolutely succeeded. It’s a very quiet film, very meditative and patient but it’s probably the biggest risk I’ve taken so far. I’m so proud of my friends who gave that film its life.

Can you open up a bit about your work and career? We’re big fans and we’d love for our community to learn more about your work.

I work in narrative cinema, shorts and features — I’m either making very violent, intense genre films or I’m slowing down for a more meditative, transcendental experience. They’re very different niches to oscillate between, and it took me a while to both find those worlds and become comfortable living in both. When you’re starting to pursue filmmaking as a career and practice as a director, you’re chasing what feels good. But that’s restricted by what type of work is familiar to you. So I started trying to emulate a lot of the action and adventure films I grew up on. It was good practice on a practical level, but the more movies I watched the more refined my taste became. I was getting introduced to legends like Bergman, Dreyer, Varda, and Wenders. And while I was learning about those styles, my work was leaning more towards some niche corners of horror like euro trash and french extremity because for me, violence is a very real thing that has powerful impact on the people we tell stories about — I care as much about what happens after the heroine rips the killer’s head off as I do watching the blood flow. They each heighten the other and I believe that’s where a lot of the value in genre filmmaking comes from. Especially if you’re using real-life situations or personalities to undergird your symbols. But it’s really dark material to wrap yourself in. When I had made a few of those, released some of that negative energy and learned more about what I liked in the practice of filmmaking, I started watching more films where I fell in love with the ethereal, transcendental beauty of something like Malick or Kieslowski. And I found that being able to swing between those two styles made each a little better — I was choreographing violence with a spiritual trajectory and release, while approaching quieter films with a surer footing of what world we were trying to transcend. That’s been the journey over the last decade of filmmaking, and it sucked. It was a lot of “hurry up and wait,” a lot of seemingly fruitless failures. But I think the greatest export from that experience has been patience with myself, with the artistic medium of cinema, with collaborators and audiences. I’ve learned the most by asking questions and listening for the long answer, or giving my team time and emotional space to discover new solutions to old problems. The world of cinema always rewards patience, and I think there’s a real spiritual connection between the two. I’m glad I worked towards that virtue. If my art is going to carry a “brand” I hope it’s labeled as by-and-for the patient and passionate.

Any places to eat or things to do that you can share with our readers? If they have a friend visiting town, what are some spots they could take them to?

I’d get out of LA! I’d either take us up to the Bay, or maybe stay in Big Bear for a while. When I’m in the city I’m either at the movies or working in a coffee shop. Most of my time in LA is spent wandering around without any specific goal, going where the vibes feel right or I hear good music. It’s not a city that makes itself easily available, and I’m aways looking for where the cracks might open and I can slip into the stream of nightlife or community. I’ve met some great friends that way but it’s not the best pitch to your friend who’s on vacation and wants the “authentic LA experience.”

Who else deserves some credit and recognition?

There’s too many people to credit! I owe my life and my art to a hundred souls who have encouraged and educated me, and I’m so lucky to still be working with many of them. Two teachers I’ve carried with me since I started pursuing film have been my high-school choreographer, Michelle Stevens, and my philosophy mentor, Peter David Gross. I learned so much about the body, about movement, inviting an audience into performance, and how to have fun under the most strenuous conditions because of Michelle. Every time I start working on a new film I find another quirk or process I inherited from her. She instilled a lot of Fosse into me, and I hold onto that dearly — especially when I’m working with actors. Peter pushed me to appreciate and question everything – art, philosophy, religion – in ways I’m still grappling with; he taught me that the best way to live is to not grow old but never stop growing up. I worried for so long that I would “run out of good art to make” and I think that’s impossible at this point. Art is the practice of exploring the human experience, reflecting itself like an infinity mirror. I could make art for eternity without ever stopping, and I don’t think I would have that confidence without either of them.

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/jessejedi/

Other: https://vimeo.com/user34536703

Image Credits

Jack Armstrong Graham Skinner Alec Salerno Bea McCormick