Meet Laura Carney | Author of My Father’s List: How Living My Dad’s Dreams Set Me Free

We had the good fortune of connecting with Laura Carney and we’ve shared our conversation below.

Hi Laura, what’s your definition for success?

Success is a byproduct. I don’t pursue anything to be considered successful or in hopes of being “successful,” but rather I focus my efforts on the story I’m writing at that moment. My chief concern is helping the world through my writing, research and reporting. I took on distracted driving at age 35, despite working in women’s magazines as a copy editor and sometimes writer for 10 years, because my dad was killed by a distracted driver when I was 25.

I wasn’t accustomed to writing about anything I had a personal experience with, but I felt the platform I’d developed by then would be helpful to something that had become a public health crisis. At that time, at least 40,000 people were dying on our roads every year. I met a number of families who’d survived these incidents, and I felt that in telling my story I was also telling theirs.

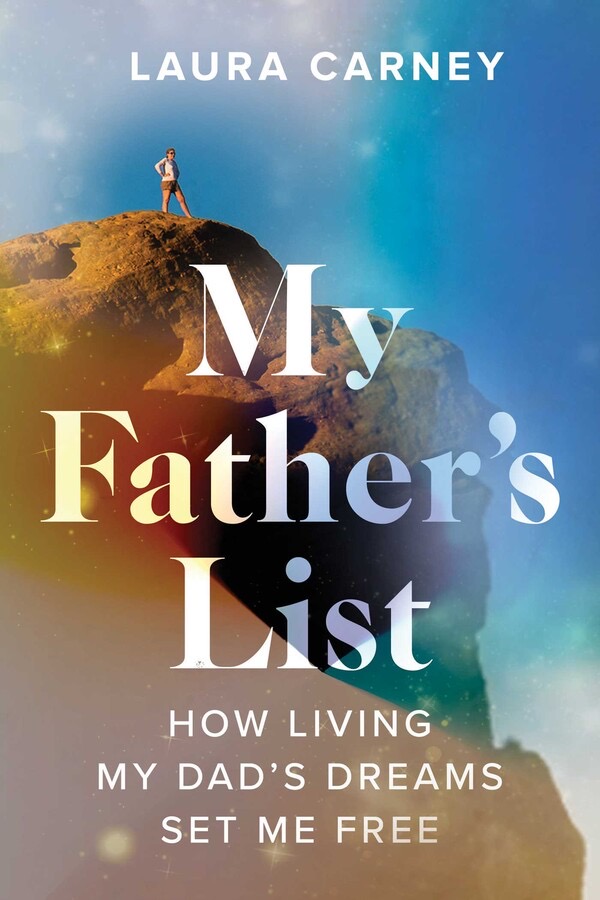

I suppose that’s the short answer to this question—for me, giving a voice to the voiceless is my definition of success. If I am helping solve problems—and now, also, helping educate and inspire people to live better lives, a side effect of finishing my dad’s bucket list for him and writing my book, My Father’s List—I feel I’ve answered my inner call. Anytime anyone answers that inner call, which is unique to them, they are automatically successful.

Can you open up a bit about your work and career? We’re big fans and we’d love for our community to learn more about your work.

I began writing creative essays around the time I graduated with a degree in English/Journalism from University of Delaware. They were often personal essays, as this was the era of the young person’s memoir—see Dave Eggers, Elizabeth Wurtzel, etc. I felt inspired by this medium, I suppose because like many writers I found it difficult to know how I really felt about something unless I wrote about it. And I loved literary journals, which embraced younger voices.

Before that time I’d only written poetry or news articles (though mostly entertainment or human interest features), and I didn’t view myself as a book writer. In fact, I’d been a visual arts major for four years, so I thought of myself more as an artist, though I enjoyed the puzzle of writing a reported article.

After I graduated, I moved to New York City for an internship in magazines. I spent the next decade climbing the ladder in that industry, finally finding myself as a full-time copy editor at Hearst (Good Housekeeping, Woman’s Day, Redbook and Dr. Oz magazines) by age 33.

I spent the next seven years working long hours (that’s just the nature of magazines) as a copy editor, and I was overjoyed for the work and to be exactly where I was, as this was my dream. I didn’t mind that I was editing more than writing, which had become my passion. I was just happy to be there. Over time I became a better writer by osmosis, just from copyediting so many articles. And I began writing TV recaps, for shows like Lost and Mad Men—oftentimes getting published by the websites of the magazines I worked for. But getting into the actual print magazine always proved difficult.

The real answer: One day the editor-in-chief asked us to submit a paragraph describing our favorite holiday memory. I submitted a story about my husband proposing on Christmas Eve, using the star we’d bought because it was like the star my dad let me put on the tree as a girl…and my father had died because of a distracted driver 10 years prior. My dad’s death was a secret I kept, so writing about it was nerve-wracking. But the editor-in-chief loved the story (I gave her a whole page) and published it, a year later, in the December issue of Good Housekeeping. In that time, I became an activist and began publishing other essays about my dad and my activism in other places, like Runner’s World and the Washington Post—big places. I was shocked how often editors said yes to these pitches. It hadn’t happened to me before. But I also hadn’t pitched very often, because I was too afraid. Something about telling my dad’s story and helping inform people about a serious problem, one that was killing people, drove me so much that I could put my fear aside.

A year later, when that first essay got published in Good Housekeeping, a social media representative for authors emailed me. She asked me to let her know when I was ready to publish a book because she’d love to represent me.

I laughed at the idea. But it stuck with me.

By now, I was about to run my first marathon (becoming a runner was part of my activism) and also about to get married. It was a very busy time. Social media took off during this time, so I used everything I was doing as content to raise awareness. When we returned from our honeymoon, I learned even more people were dying because of distracted driving. I thought back to what that social media rep for authors had said. I started thinking that if only I could write a whole book about my dad, maybe his story would connect enough that it might save people from his fate.

Then one day, six months after my wedding, my brother discovered what looked like our dad’s bucket list. It had been hidden for over 13 years. Nobody knew he’d even had a bucket list, except my mom—and since he wrote it when he was 29, and they divorced six years later, she didn’t know my dad had continued checking off the list his whole life.

As soon as we saw the list at my brother’s house, we knew I needed to finish it—and write about it.

This was the book I was supposed to write.

I think sometimes when we pursue something creatively like this, a lot of it comes from setting up the right circumstances to receive the call. For example, I’d been building a life at that point where in addition to my regular job, I was running regularly, publishing articles in big places regularly and helping people through my activism. I’d also become a person who’d given up even social drinking. I’d started taking painting classes again. I was highly engaged in life when the idea to write a book came. And because I was always seeking for a way to do this, when I was ready, the list appeared. Getting married also had a lot to do with it—through planning my own wedding, and training for a marathon simultaneously, I’d demonstrated that I now had the patience to take on a project like this.

And boy did it take patience. Even though the list was life-changing and fun and thrilling most of the time, the reality is that taking on 54 dreams of your father’s over a six-year period requires a lot of patience, a lot of sacrifice and a lot of faith. Most of the time I had no idea how I would do certain list items, and I just had to believe that I was being led by something bigger than me—that my dad and the divine wanted me to do this. The sooner I looked at what I was doing as serving something greater, and surrendered to that process, the easier it got. Finishing my dad’s bucket list also helped me shed bad habits and limiting beliefs that had prevented my success creatively in the past. I had to move beyond self-doubt and believe I could do things like write a book, speak on TV, jump out of an airplane, surf in the Pacific, sail by myself, go to the Super Bowl, etc. Every list item brought new reasons why I believed I couldn’t do something, and I had to just look at whatever the list item entailed as an interesting experiment, one in which I’d probably embarrass myself, but that was all part of it. The risk-taking and faith the journey required was really just an expression of love for my father. And this was why I was able to move past my anger over his death. Here he had died for a pointless, preventable reason—a teenager making a phone call while driving—and here I was doing something meaningful and deliberate to honor him, quite the opposite of how he had died. It helped me reframe the story, something I needed to do—I’d allowed myself to feel I was disposable or unlucky too, like I thought he was, but my success with the list was now proving otherwise. And when I say “success,” I don’t mean checking off each item—the real success was both beginning and refusing to give up. That was what was most valuable about what I did. Because my faith that my dad and God wouldn’t let me fail gradually morphed into a strong faith in myself—that I would not let me fail. And now I apply that strong self-belief to any project I take on.

It’s how I was courageous enough to handle being on TV shows like CBS Sunday Morning, Tamron Hall and now Jake Tapper on CNN, to talk about my experiences. I know every time I speak publicly about what I learned from checking off the dreams a man wrote down in 1978, I’m not only teaching about legacy and the desire to solve a deadly problem but also about the value of mindfulness, intention and living a fulfilling life. The value of belief! We have to believe we can do what we set out to do, regardless of the current state of the world. When my dad wrote his list, the world was a mess then too.

I started out on this journalistic project coaching myself to be brave enough to write about a personal nightmare….but I came out the other side as an expert on realizing dreams. What a transformation!

What I want young artists to understand most is how important it is to believe in your own dreams and persist in seeing them through, even if they seem crazy to everyone. In the end, your life will have been yours to live, and you will have to ask yourself, did I do what I wanted with it? Life is unpredictable, we can go at any time. My dad died surprisingly at 54. Don’t you want to make the most of it? To actually feel alive while being alive? For an artist that means making things. Not sitting on your phone two hours a day.

Also, remember that first impressions are usually not fully informed. We are living in a time where you can Google anything and have constant access to entertainment—this can lead to the notion that we all know more than we do, and can lead to apathy. A lack of inspiration. You have to go off the beaten path to find new ideas, leave something up to chance. And the truth is, our first hunches about things are usually wrong. I thought the football items on my dad’s list would not be enjoyable. But then I found myself a huge football fan. I thought I’d hate the golf item—but it ended up being exciting. Sailing was an entirely different animal than I thought it would be. And meeting a president and corresponding with the pope involved learning things I couldn’t have known. The truth is, it’s these moments of discovery that shape us into the creatives we are supposed to be. We should always maintain beginner’s mind. Always learning about something new, something we will use in our artistic expression later, reminding ourselves the world is a beautiful, magical place, where anything truly is possible.

And finally, remember that just because people think your idea is crazy now, doesn’t mean you won’t find the people who help you bring it to life. They’re out there. So many people helped me with my dad’s list. And with the book. I found the allies I needed. I just had to take the first step.

Let’s say your best friend was visiting the area and you wanted to show them the best time ever. Where would you take them? Give us a little itinerary – say it was a week long trip, where would you eat, drink, visit, hang out, etc.

My favorite spot in Los Angeles is technically in Pasadena—the Huntington. But I love the L.A. Botanical Garden too. I’m just a big garden person. But of course I’d also take them to Santa Monica and Venice Beach, the Getty Museum, up the Pacific Coast Highway to see Hearst Castle, and out for a hike in the Santa Monica Mountains (the cover of my book, My Father’s List, is actually me standing atop Eagle Rock, looking at the Pacific Ocean). I’d also take them to see the stars in downtown Hollywood or to a show at the Pantages. Definitely for a meal at Veggie Grill, or maybe at Yamashiro. And a trip to Greystone Mansion is a must. I also love the Academy Museum and the Museum of Jurassic Technology. Oh, and the Hollywood sign! A crucial character in my book! Zibby’s Bookshop is a very cool bookstore in Santa Monica where I got to host a reading on my book tour. Oh, and for food I also love Sugarfish for sushi and Cafe Gratitude for a fancy sit-down vegan meal. And for sweets—Chaumont Vegan, which has gold-encrusted chocolate orange croissants, and Donut Friend all the way. We also always enjoy a trip to the Farmers’ Market. And stay on Sunset Blvd! Best Western Sunset Plaza hotel, all the way! (The Avalon in Beverly Hills is also very nice. It’s where Marilyn Monroe lived!)

Who else deserves some credit and recognition?

Every person who helped me finish my dad’s bucket list.

Website: https://bylauracarney.com

Instagram: myfatherslist

Linkedin: Laura Carney

Twitter: myfatherslist

Facebook: myfatherslist

Image Credits

For the tuxedo photo, Adrian Bacolo. All others courtesy Laura Carney.